Commentary

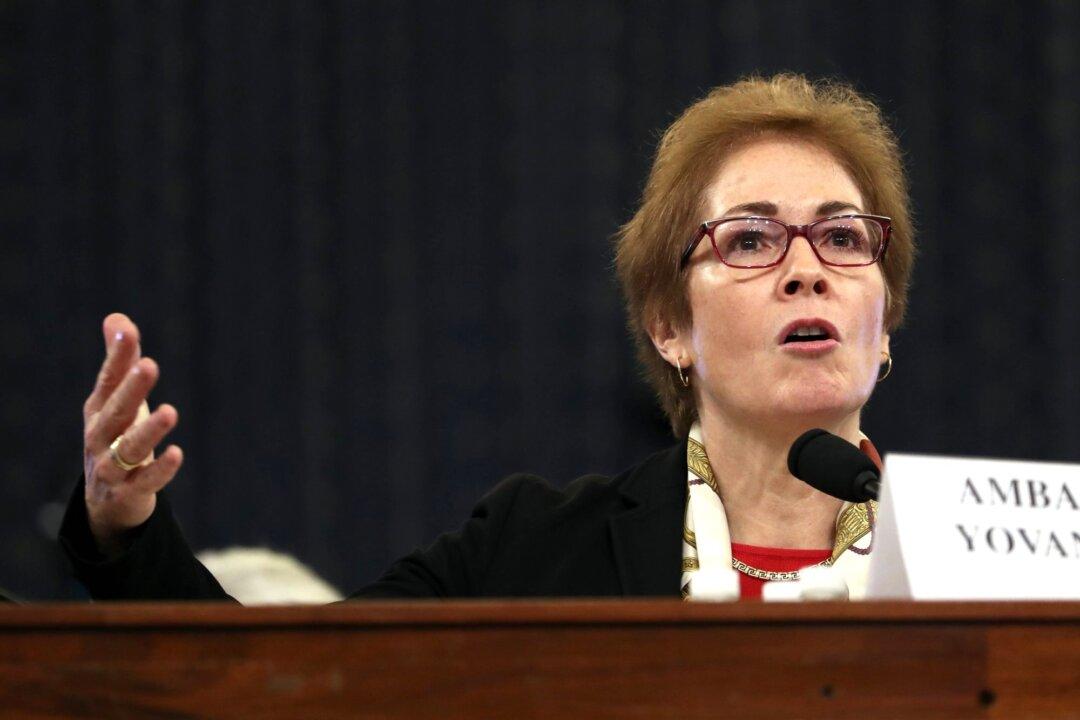

On Nov. 15, Marie Yovanovitch, the former U.S. ambassador to Ukraine, publicly testified at the impeachment hearing involving President Donald Trump.

On Nov. 15, Marie Yovanovitch, the former U.S. ambassador to Ukraine, publicly testified at the impeachment hearing involving President Donald Trump.