Commentary

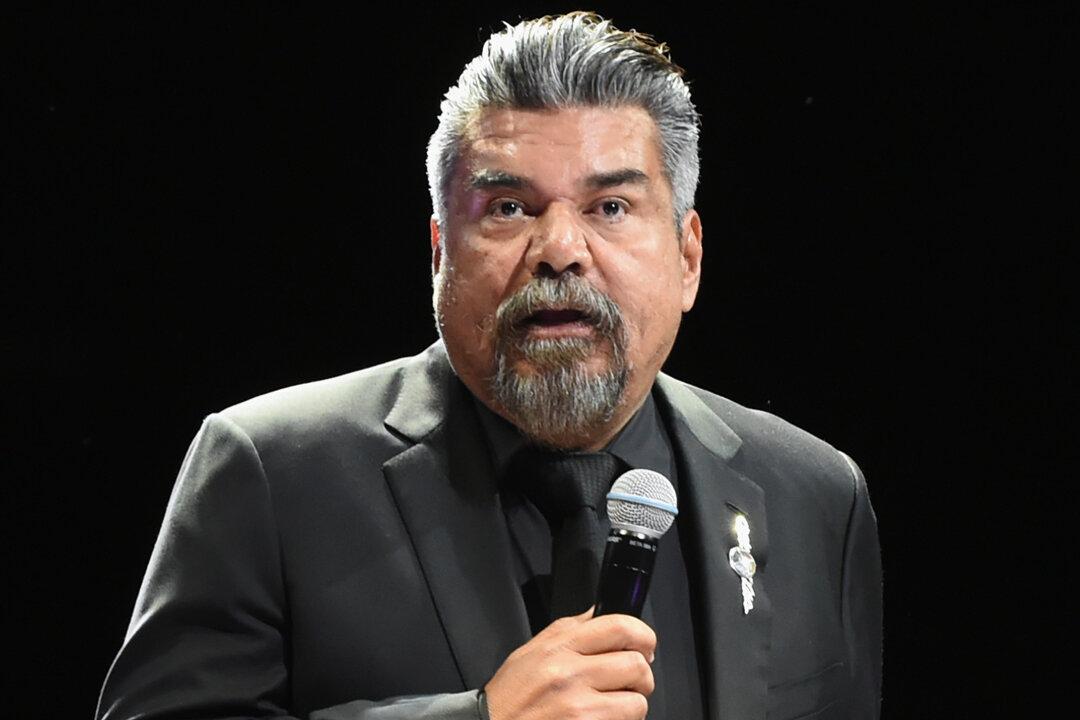

Comedian George Lopez recently came under fire after he joked about an $80 million bounty that was placed on President Trump’s head.

Comedian George Lopez recently came under fire after he joked about an $80 million bounty that was placed on President Trump’s head.