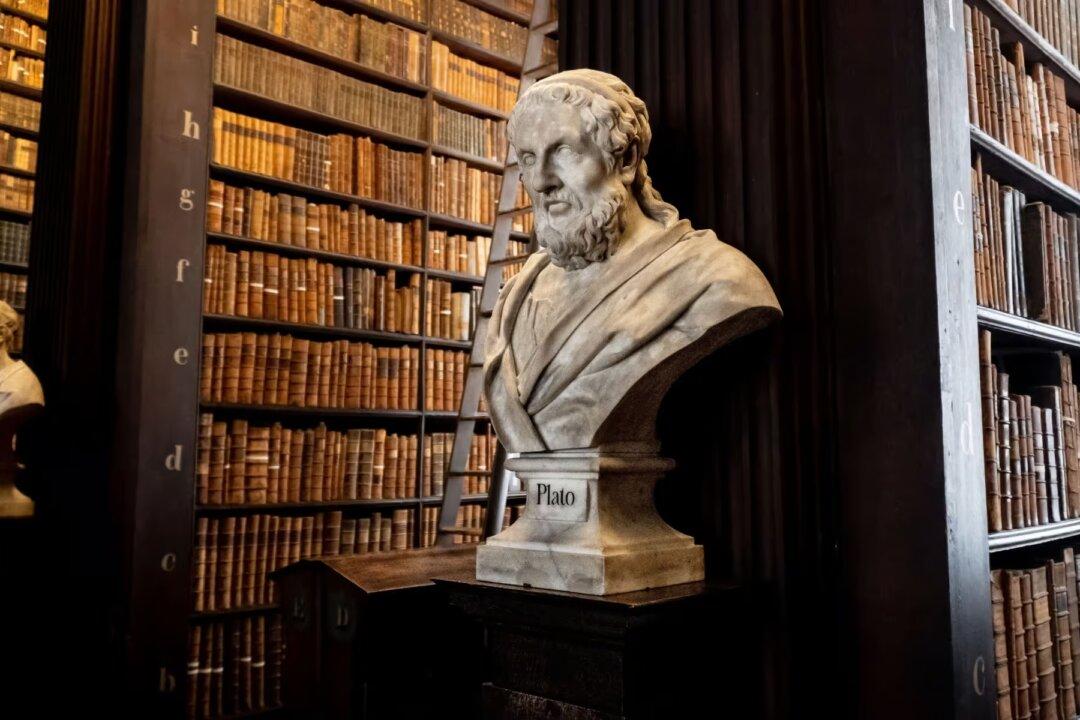

Commentary

It would seem as if Martin Heidegger’s warning against the “essence of technology”—“Gestell,” or Enframing—a way of thinking that frames everything we think of, do, and aspire to, in terms of parameters of optimal use or control, was no illusion, judging by evidence of such attempts today. Apparently engineering researchers at Northwestern University have managed to develop and construct the first flying microchip in the world. But instead of implementing this astonishing feat for the improvement of people’s lives, the opposite seems to be the case.