Everything we do as humans is provisional. Because of time’s eroding power, everything is revisable. There is a reason for the word “decision” being a part of our language. Not accidentally, the term derives from the Latin for “cut”; in other words, when we decide something, we make a volitional cut of sorts in the sequence of events, or in the reasoning concerning such events, that precede the decision—a concrete reminder that human beings are not equipped with an algorithmic device that enables them to know with absolute certainty what course of action to pursue. Every decision, therefore, represents an acknowledgment that we have to act with incomplete, provisional knowledge, and by implication, that more information and more comprehension could lead to a different decision.

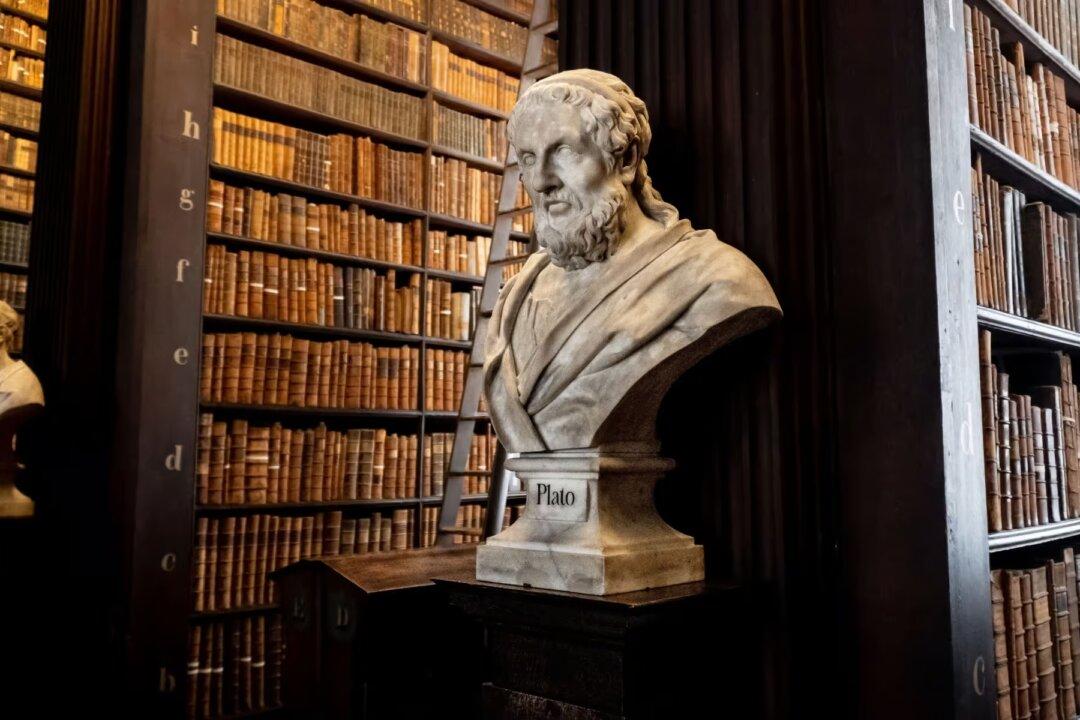

The marble bust of Plato by Peter Scheemakers among an enormous collection of old books in the Long Room at Trinity College’s Old Library legal deposit or copyright library, in Dublin on Oct. 1, 2023. EWY Media/Shutterstock

Commentary

Bert Olivier works at the Department of Philosophy, University of the Free State. Bert does research in Psychoanalysis, poststructuralism, ecological philosophy and the philosophy of technology, Literature, cinema, architecture, and Aesthetics. His current project is “Understanding the subject in relation to the hegemony of neoliberalism.”

Author’s Selected Articles