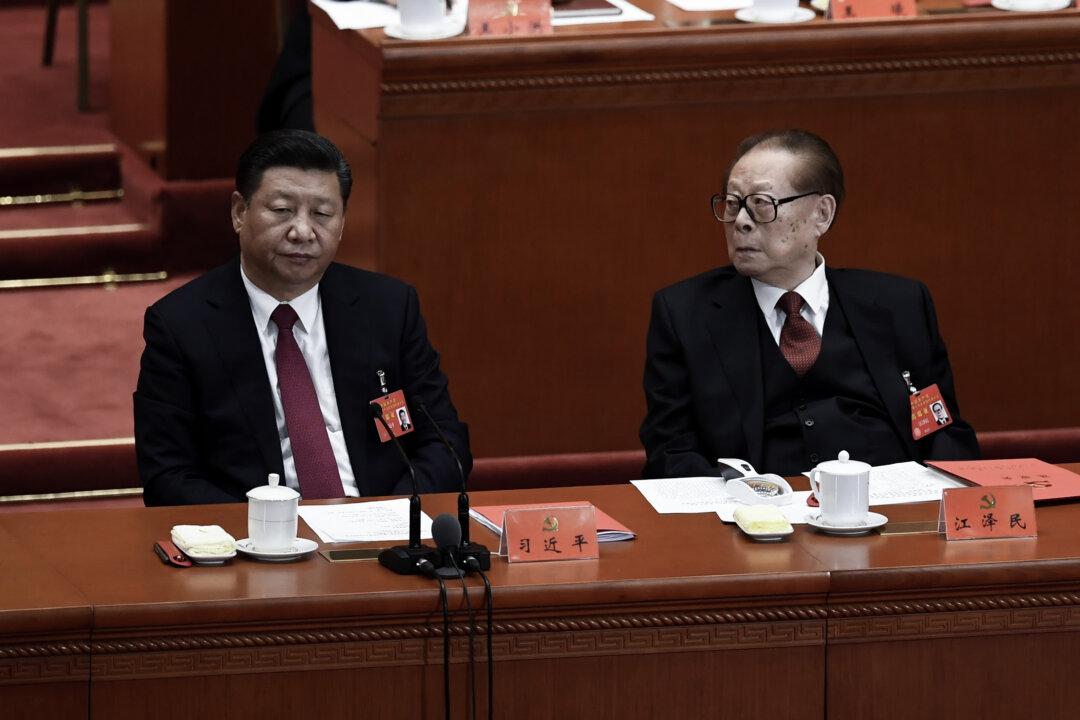

Jiang Zemin’s death (1926–2022) is an appropriate occasion to reflect on his historical significance as the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 1989–2002 and as chairman of the Central Military Commission from 1989–2004.

His rule defined the “third generation” of Party leaders. It was defined by great support for business, the emphasis on economic growth at any cost, endemic corruption, human rights abuses, including the persecution of Falun Gong, and religious and political freedoms more broadly.

Jiang was often perceived as a rather eccentric leader by the standards of the Chinese regime who started his career as a technocrat and mayor of Shanghai, elevated by Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s to foster economic reforms, including the privatization of state-owned enterprises—all of which contributed to China’s growth.

But what truly generated China’s rise during Jiang’s tenure were four major events.

During Jiang’s tenure, the Clinton administration—which had been elected after blaming George H.W. Bush’s administration for “coddling dictators from Baghdad to Beijing”—abandoned the linkage between human rights in China and the renewal of Most-Favored-Nation status. This greatly weakened the ability of the United States to force political change on the Chinese regime and allowed Jiang to realize his goal of economic reform without political change.

Second, the Clinton administration supported China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in December 2001. This allowed China into the West’s economic ecosystem and ensured that its economic might could be siphoned off to support the expansion of its military capabilities and diplomatic influence in global politics.

Third, the seeds of elite capture were sown by the Clinton administration’s “coffee klatches” and other meetings beginning in 1995 that traded political influence in the United States for donations to the Democrat National Committee and other financial and political support, while U.S. firms traded with China and invested in China’s growth. Even U.S. defense contractors did so; notably, the major defense firm Loral Corporation was accused of defense technology transfer to China in 1996.

Fourth, Hong Kong was returned to Chinese rule from Great Britain in 1997, and Macau from Portugal in 1999.

The death of the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, this summer, is also relevant to Jiang’s legacy. The Chinese regime was determined not to repeat what they perceived to be Gorbachev’s fundamental mistake: his attempt at political reform in the Soviet Union. The CCP saw that as the cause of the Soviet Union’s collapse.

Thus, Gorbachev’s true legacy is not found in the West but in China—instructing Deng and Jiang what not to do. Deng and Jiang learned from Gorbachev that the CCP must never enact political reforms, only economic ones, and that the Chinese, unlike the Soviets, must enter the Western economic ecosystem to become strong enough to overthrow the West. Thus, Gorbachev did not end the Cold War, but as China’s tutor and its canary in the coal mine of hazards of reform in communist systems—he contributed to the origins of a new one.

Like Gorbachev, Jiang received excellent press as a heroic figure in the case of Gorbachev or an enlightened ruler bringing wealth to China, a transition from Deng to Hu Jintao’s rule, and establishing some degree of order for the Party’s leadership transitions.

In fact, while Deng was the murderer of political reform in China, Jiang was its undertaker. Moreover, Jiang engineered Deng’s design to penetrate the United States, Western, and other governments and centers of influence around the world. This was a singularly effective strategy for permitting China to rise without generating the counterreaction from other great powers that should be expected based on the balance of power politics.

The insistence of Western media, analysts, and government officials to fetishize rulers like Gorbachev or Jiang—that he is relatively young, drinks scotch, or loves the arts and singing—are symptoms of the deeper problem. That is the inability to understand the hostile intent and deviousness of these individuals and the ideology they represent. Thus, Jiang’s historical legacy should be seen for what it was.

As China’s economy was booming, he had the perfect opportunity to improve human rights in China, and he did not, just the reverse. He had the chance to advance political reform, and he did not. He had the occasion to improve relations with China’s neighbors, solving the border disputes with India and in the South China Sea, and he did not. Having incorporated Hong Kong and Macau, he might have secured the rights of their residents to make it more difficult for the current CCP leader, Xi Jinping, to crush their human rights. He might have provided assurances to Taiwan but did not. He had the opening to slow China’s military buildup and failed to do so. Instead, he did what a faithful communist would do.

Jiang was a loyal servant to Deng’s ambitions; he furthered those ambitions and exploited the avarice of politicians, captains of industry and technology, and opinion makers the world over. China’s military power, which is now on full display, did not spring like Athena from Zeus’s head, but took decades to create. Jiang largely laid the foundation.

The aggressiveness of Xi is possible because of the actions Jiang undertook. The genocide against Muslims in Xinjiang is possible because of the tools Jiang provided.

Viewed from a historical perspective, he was a capable leader who advanced the strength of the Chinese regime and exploited the avenues provided by other countries. Jiang might have made great changes to improve the political life of the Chinese people after Deng’s death. He did not. In his personal life, he might have been a thoughtful, even a renaissance man, and he certainly played on this to influence international audiences. But in his public life, he was a loyal paladin and effective leader of an odious and thuggish regime.