Commentary

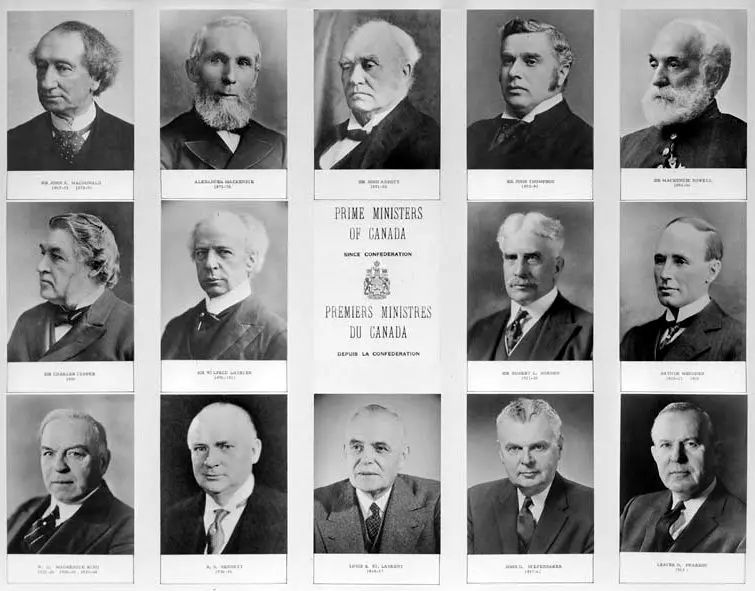

Sir John Sparrow David Thompson (1845–1894) was Sir John A. Macdonald’s most skilled protégé and was prime minister from 1892 to 1894. But he had the tragic honour of being Queen Victoria’s only first minister to drop dead in the royal presence. He was 49, and his embarrassed last words were: “It seems too absurd.”