Commentary

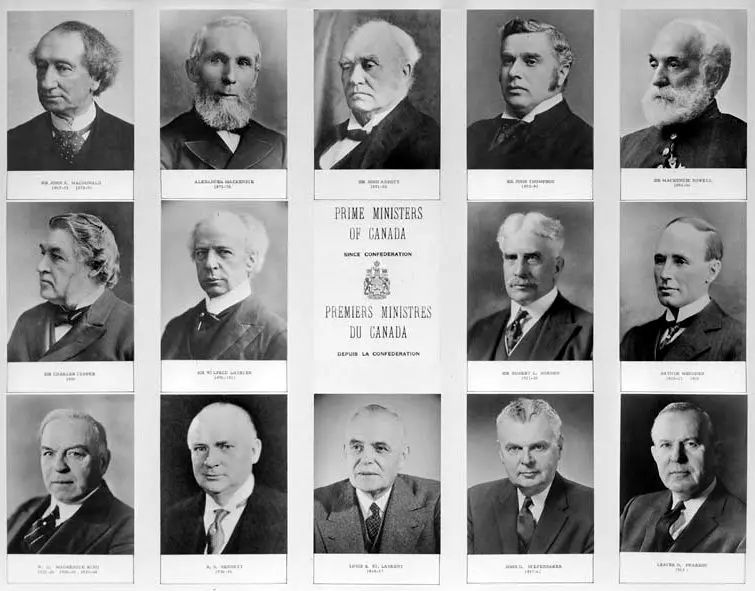

Sir Charles Tupper pulled an all-nighter on the evening of his first political meeting on Oct. 10, 1844, in his hometown of Amherst, Nova Scotia. The occasion was a debate between Joseph Howe, the famous opposition leader, reformer, and “Father of Responsible Government,” and Alexander Stewart, a senior Conservative and legislative councillor who served in the province’s venerable upper house. (Back then, most provinces had their own senate.)