Commentary

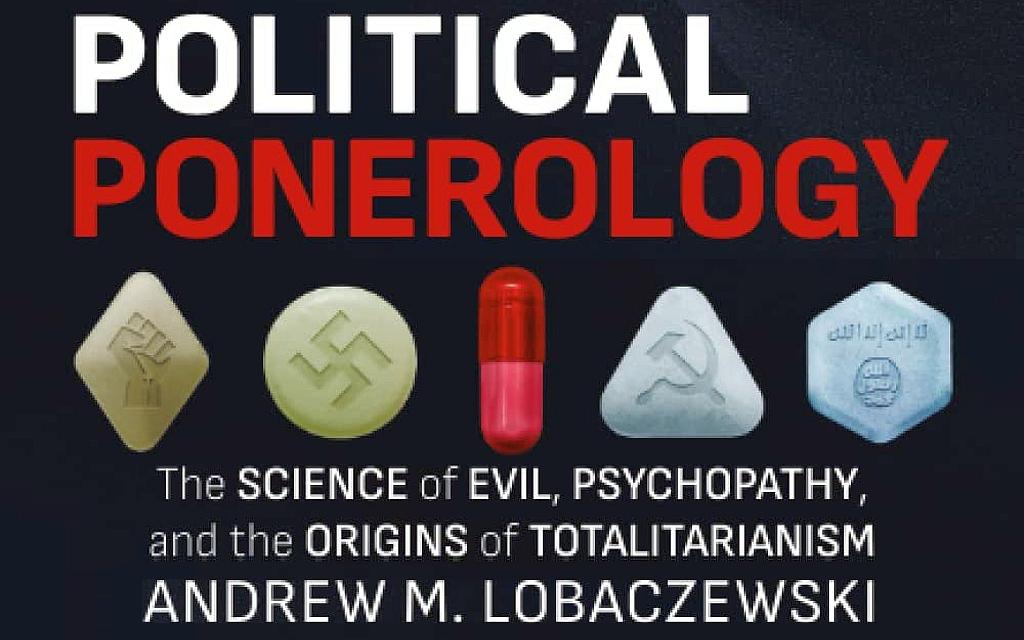

A new edition of “Political Ponerology,” by Andrew M. Łobaczewski, edited by Harrison Koehli, is now available on Amazon.[1] This strange and provocative book argues that totalitarianism is the result of the extension of psychopathology from a group of psychopaths to the entire body politic, including its political and economic systems. “Political Ponerology” is essential reading for concerned thinkers and all sufferers of past and present totalitarianism. It is especially crucial today, when totalitarianism has once again emerged, this time in the West, where it is affecting nearly every aspect of life, including especially the life of the mind.