In “1984,” George Orwell cautioned us, “The most effective way to destroy people is to deny and obliterate their own understanding of their history.” Orwell further pointed out: “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.”

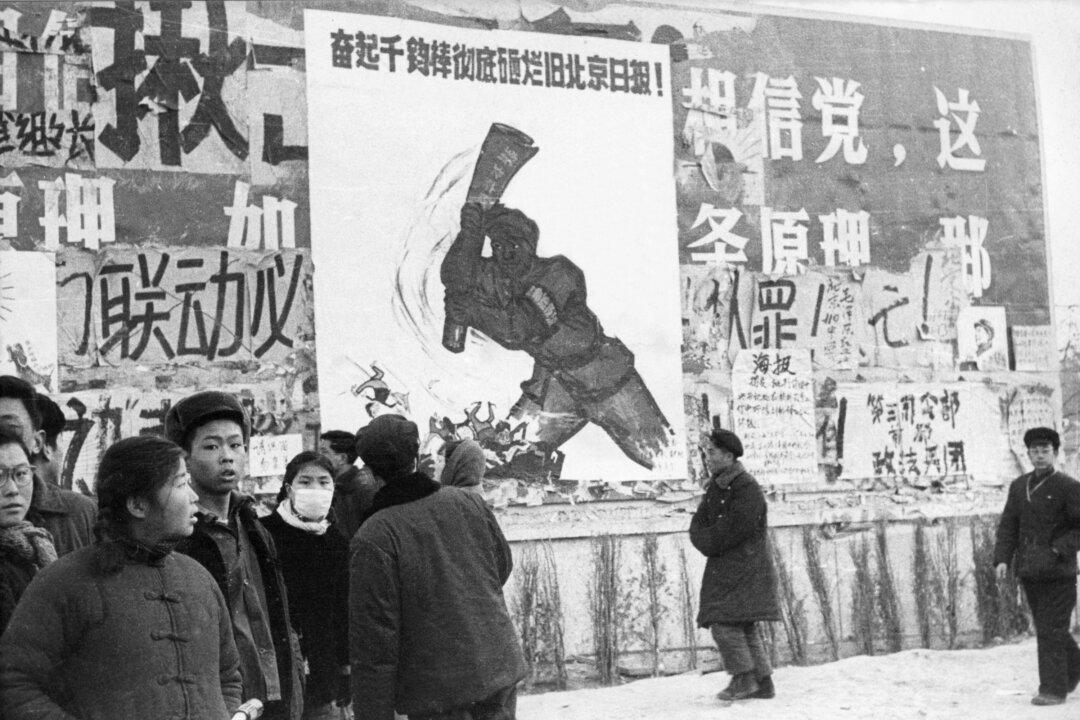

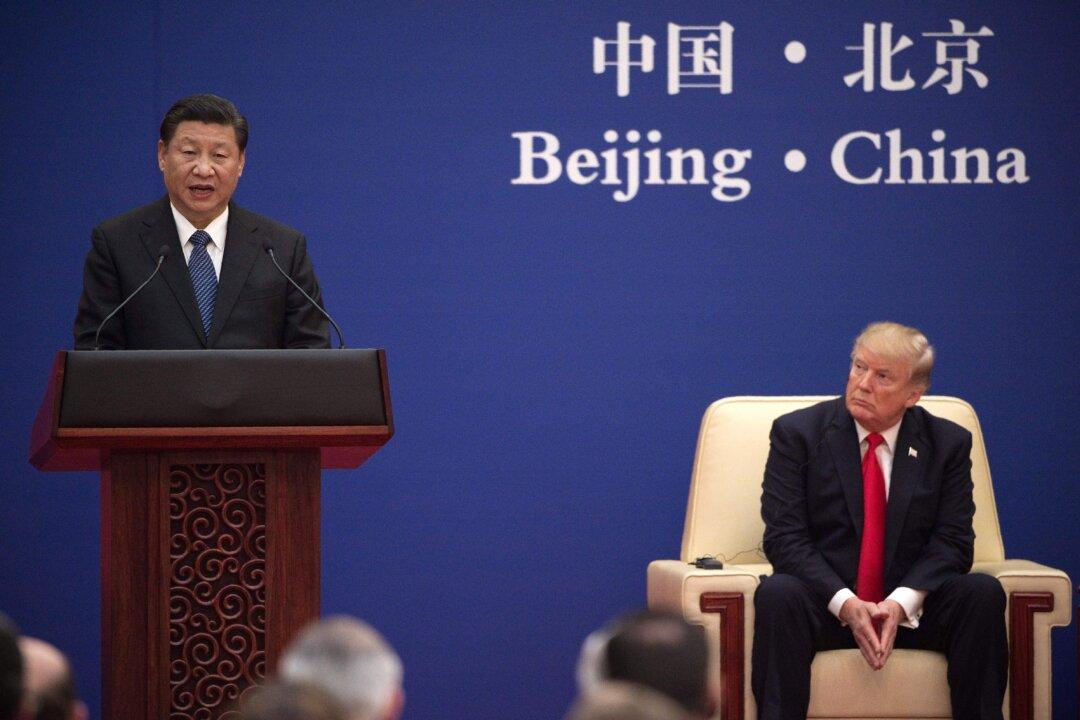

Perhaps, no entity better practices Orwell’s dictum than the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). If you live in China long enough, chances are you will likely witness the CCP revising its own history periodically, depending on its leaders’ political needs or perhaps mood swings.