Commentary

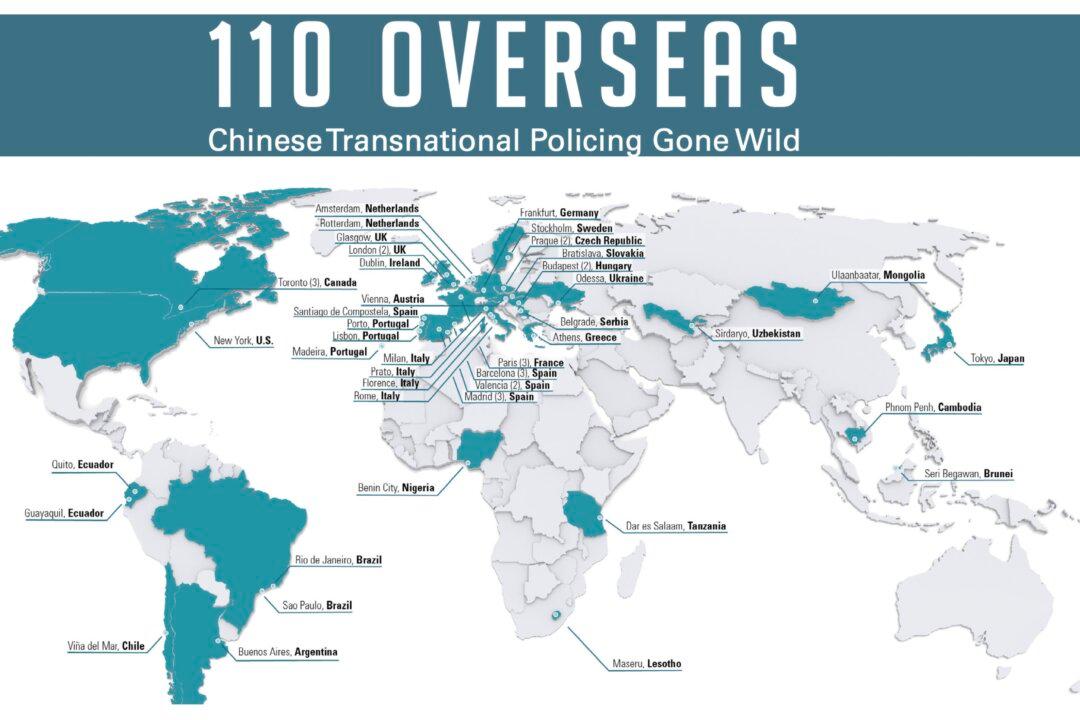

The well-researched report, “110 OVERSEAS: Chinese Transnational Policing Gone Wild” (hereafter, the Report), released in late September by Safeguard Defenders, a human rights NGO based in Madrid, rang alarm bells in democratic countries already on heightened alert because of the pervasive Chinese infiltration of their political, social, and economic spheres. The Report detailed how the Chinese regime has been setting up quasi-police stations in major cities in democratic countries to coerce the return of Chinese immigrants it deems to be criminals so they can be arraigned in China. Most important among those targeted persons, though not necessarily most numerous, are political and ethnic dissidents.