Commentary

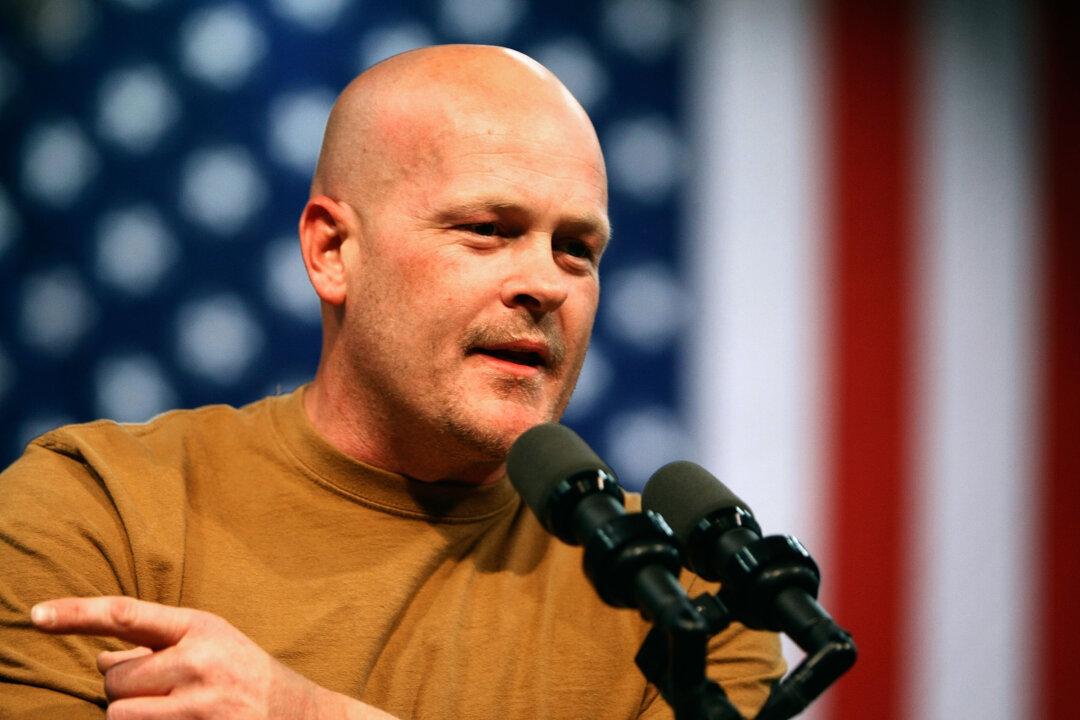

The news that Samuel Joseph Wurzelbacher, known the world over as “Joe the Plumber,” had died at age 49 brought me back to the bad old days of 2008.

The news that Samuel Joseph Wurzelbacher, known the world over as “Joe the Plumber,” had died at age 49 brought me back to the bad old days of 2008.