Commentary

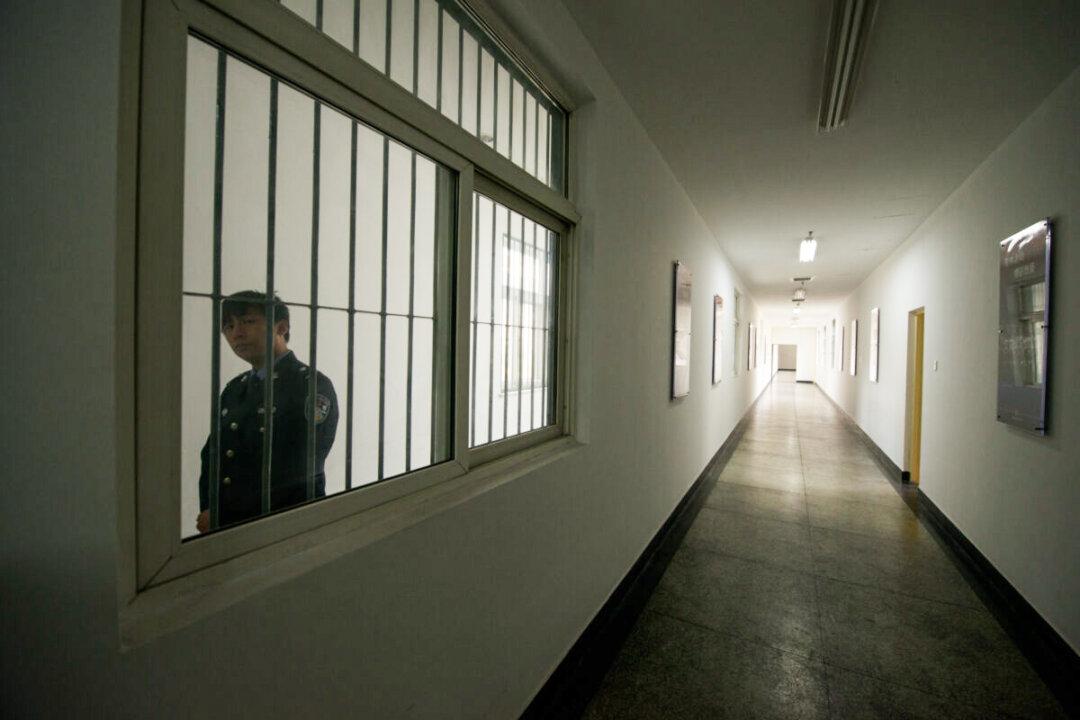

China’s communist regime has wrongfully detained as many as 200 Americans, according to a nonprofit humanitarian organization cited by Reuters on Jan. 18. As the country ends its COVID-19 lockdowns and again tries to attract tourists and businesses, they should realize that it’s an exceedingly unsafe country.