Commentary

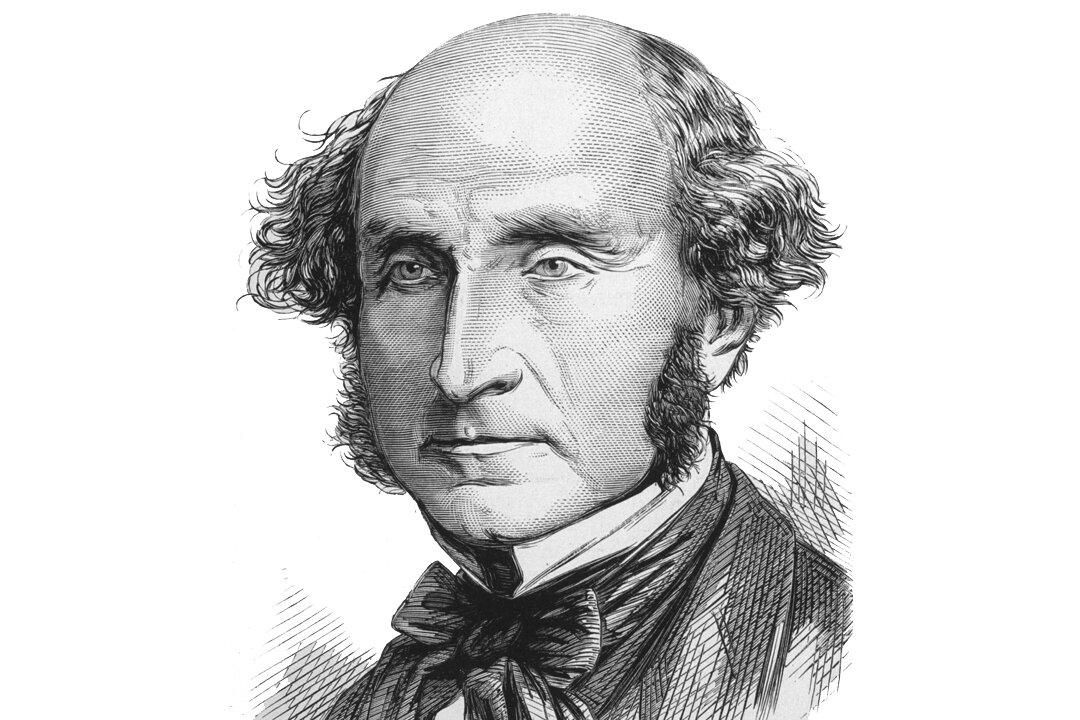

I’ve expended a fair amount of ink criticizing John Stuart Mill’s ideas about liberty in his (in)famous 1859 pamphlet “On Liberty.”

I’ve expended a fair amount of ink criticizing John Stuart Mill’s ideas about liberty in his (in)famous 1859 pamphlet “On Liberty.”