Commentary

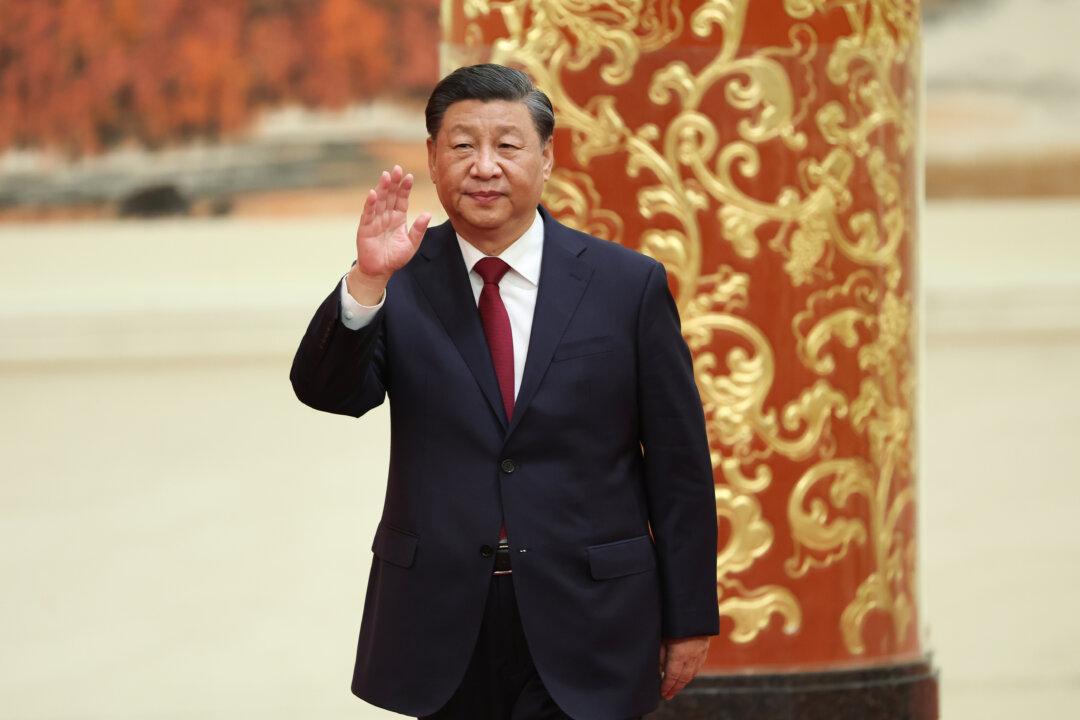

Financial markets have shown disapproval of Xi Jinping’s success in securing a third term as China’s leader. Stocks, bonds, and China’s currency, the yuan, all fell with the close of the Party Congress and have more or less stayed down. The reaction is certainly understandable. For some time now, Xi has shown a penchant for policies that can only be described as anti-growth. His continuation in power can only mean more of the same.