Commentary

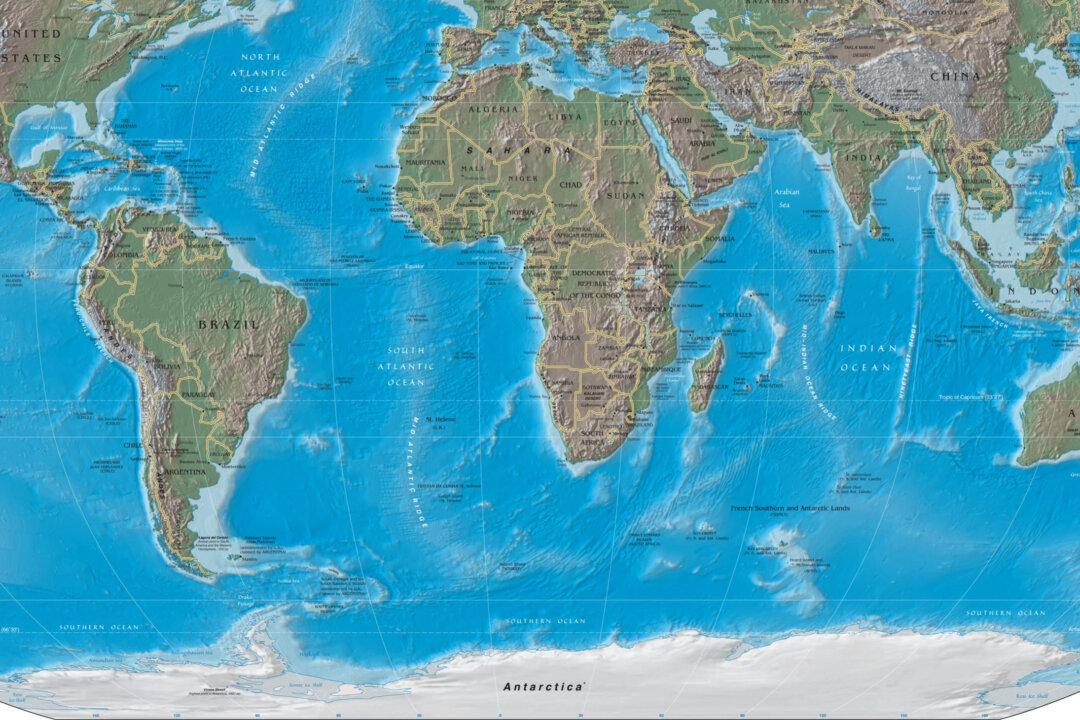

Electric vehicles (EV) are a poster child for the so-called green transition. Even in some of the world’s poorest economies, an unquestioning embrace of all things “green” on the part of political elites powers a push for the adoption of electric vehicles.