News Analysis

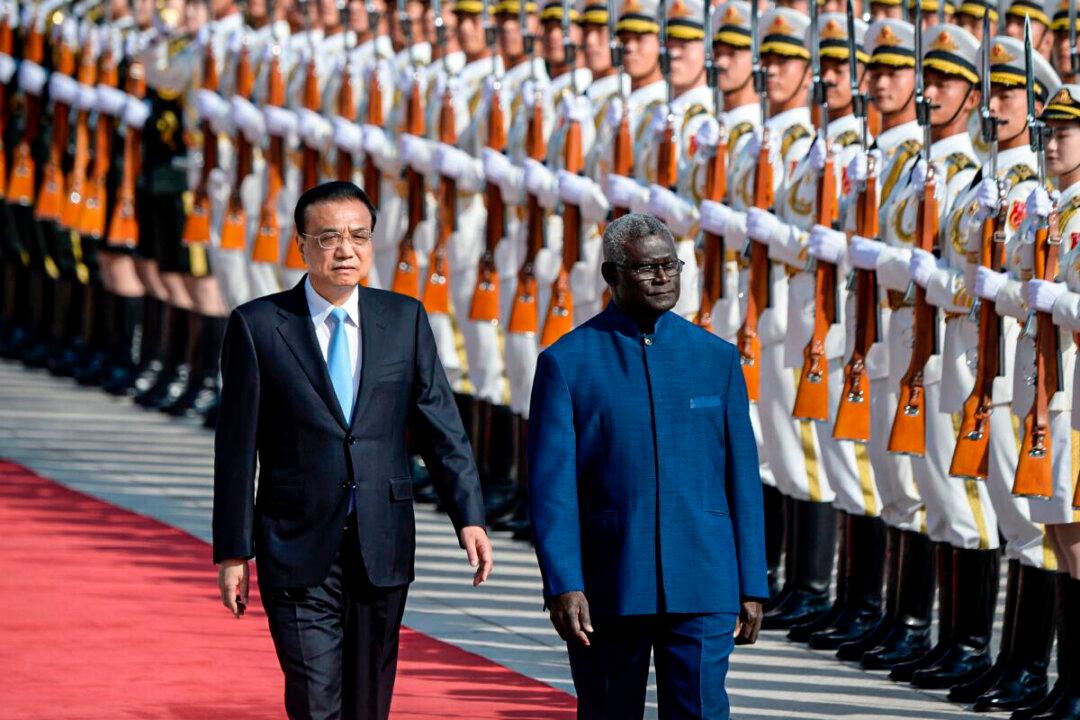

New documents show that China seeks to expand its influence and military deployments in the Asia-Pacific islands nearly to the point of making one country, the Solomon Islands, into a vassal state.

New documents show that China seeks to expand its influence and military deployments in the Asia-Pacific islands nearly to the point of making one country, the Solomon Islands, into a vassal state.