Commentary

Thinking About China

Opinion

China Issues Dollar Bonds in Saudi Arabia—A Strange Move

China has floated a $2 billion bond issue in Saudi Arabia. That Beijing chose Riyadh and denominated the bonds in U.S. dollars says a lot.

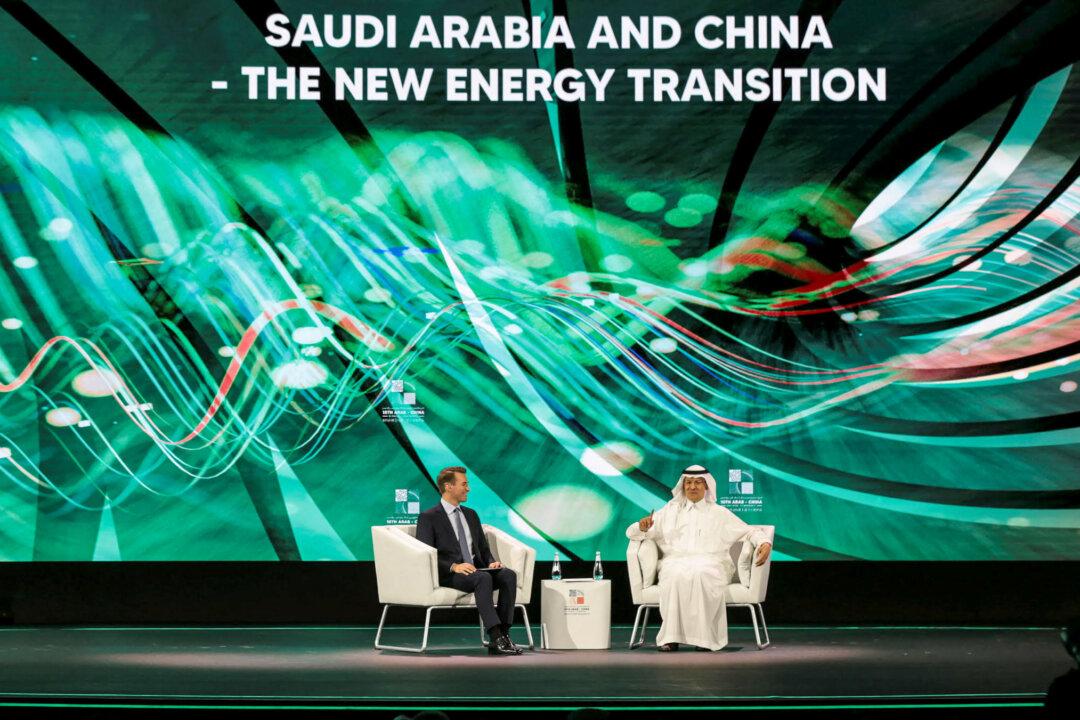

Saudi Arabia's Minister of Energy Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman Al-Saud speaks during the 10th Arab-China Business Conference in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, on June 11, 2023. Ahmed Yosri/Reuters

Milton Ezrati is a contributing editor at The National Interest, an affiliate of the Center for the Study of Human Capital at the University at Buffalo (SUNY), and chief economist for Vested, a New York-based communications firm. Before joining Vested, he served as chief market strategist and economist for Lord, Abbett & Co. He also writes frequently for City Journal and blogs regularly for Forbes. His latest book is “Thirty Tomorrows: The Next Three Decades of Globalization, Demographics, and How We Will Live.”

Author’s Selected Articles