One of the most famous articles in economics, written by Milton Friedman and published in The New York Times, states: “The businessmen believe that they are defending free enterprise when they declaim that business is not concerned ‘merely’ with profit but also with promoting desirable ‘social’ ends; that business has a ‘social conscience’ and takes seriously its responsibilities for providing employment, eliminating discrimination, avoiding pollution and whatever else may be the catchwords of the contemporary crop of reformers. In fact they are—or would be if they or any one else took them seriously—preaching pure and unadulterated socialism. Businessmen who talk this way are unwitting puppets of the intellectual forces that have been undermining the basis of a free society these past decades.”

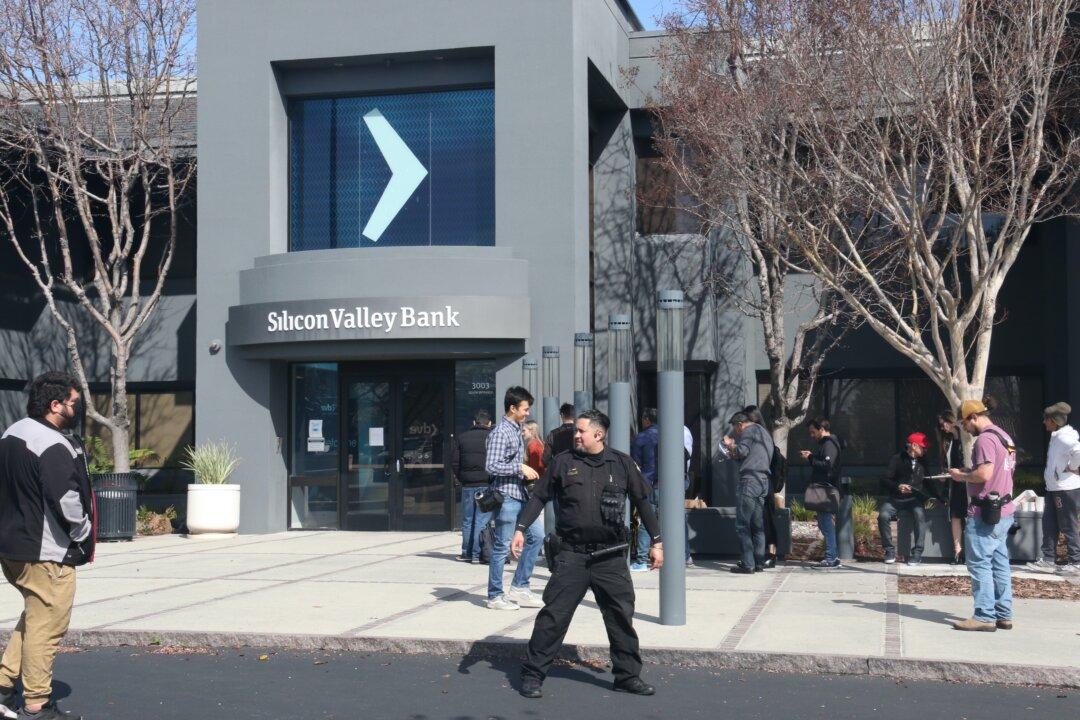

Customers wait in line outside the shuttered Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) headquarters in Santa Clara, Calif., on March 13, 2023. Vivian Yin/The Epoch Times

Commentary

David Parker is an investor, author, jazz musician, and educator based in San Francisco. His books, “Income and Wealth” and “A San Francisco Conservative,” examine important topics in government, history, and economics, providing a much-needed historical perspective. His writing has appeared in The Economist and The Financial Times.

Author’s Selected Articles