Commentary

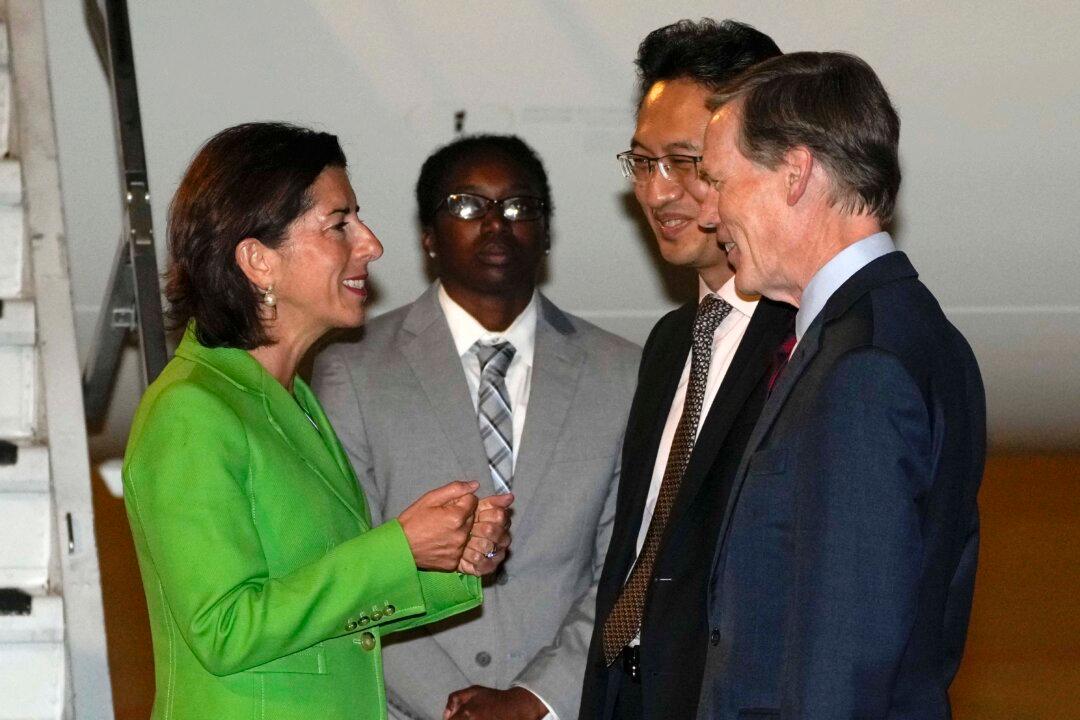

Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo visited China at the end of August to discuss improved trade relations. She’s the third cabinet-level official to make the trip in the past few months. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen preceded her, and Secretary of State Antony Blinken preceded Ms. Yellen. All three visits clearly mean to prepare the ground for a meeting between President Joe Biden and Chinese leader Xi Jinping this November, when both attend Asia-Pacific cooperation meetings in San Francisco.