Commentary

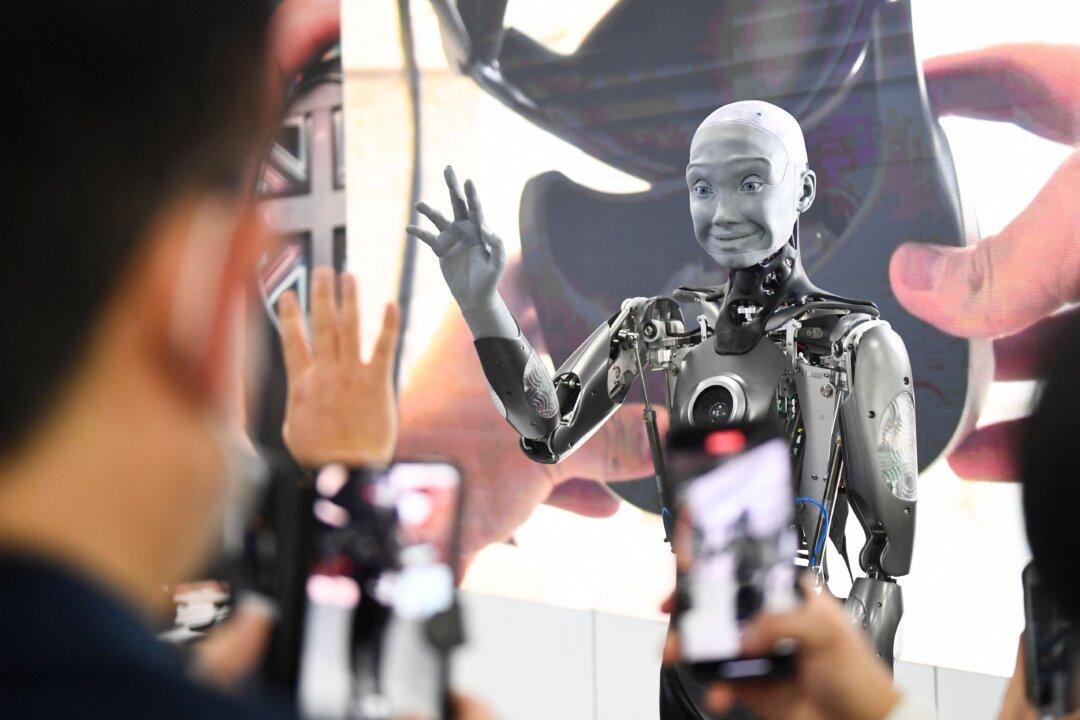

Artificial intelligence (AI) has created some enthusiasm and even more fear. The fears center partly on matters of privacy and the upending of social relationships, but mostly on job destruction.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has created some enthusiasm and even more fear. The fears center partly on matters of privacy and the upending of social relationships, but mostly on job destruction.