Commentary

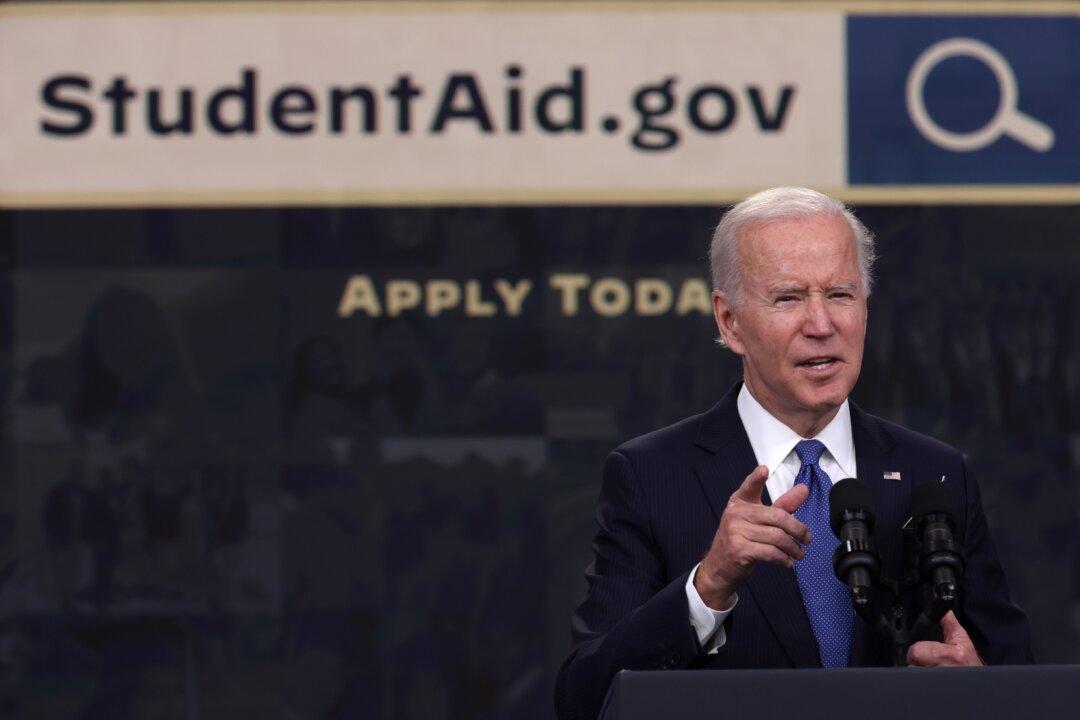

After losing at the Supreme Court, President Joe Biden has floated another student debt relief scheme. Lawyers and judges will take a while to decide if this new approach passes constitutional muster, no doubt, until after the 2024 election. But while the legal gears turn—slowly as ever—the political-economic implications will emerge immediately and be the same as last time.