Commentary

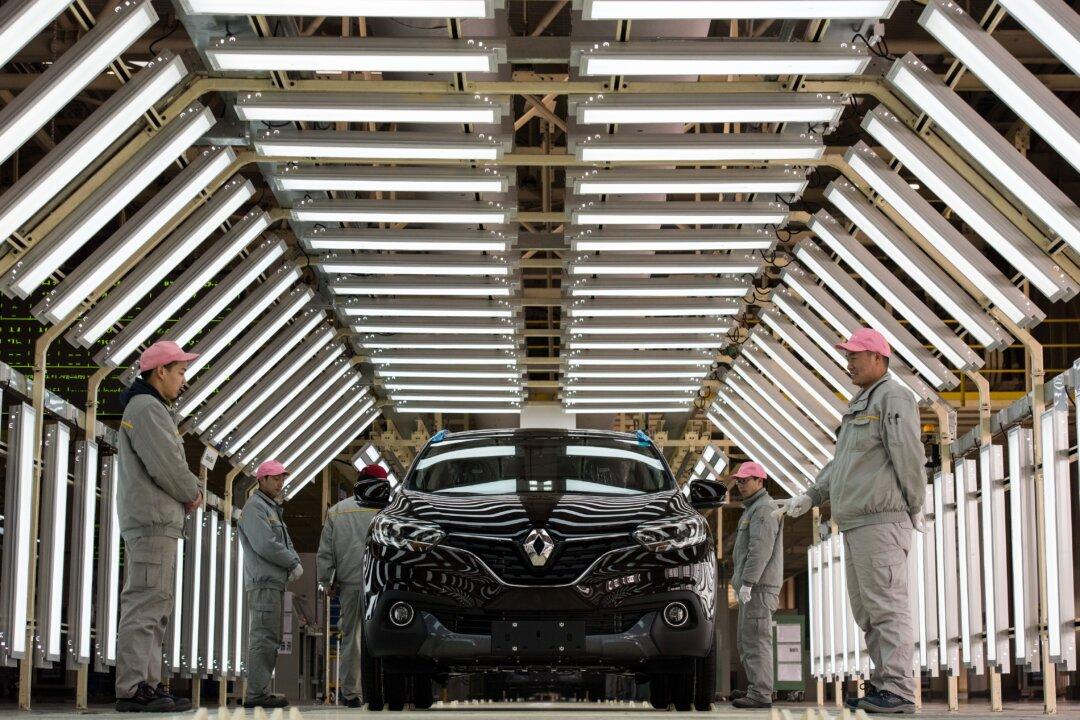

Foreign direct investment (FDI) into China has picked up markedly in this post-pandemic environment. It has even surpassed foreign investment into the United States, and the American media has made much of that fact.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) into China has picked up markedly in this post-pandemic environment. It has even surpassed foreign investment into the United States, and the American media has made much of that fact.