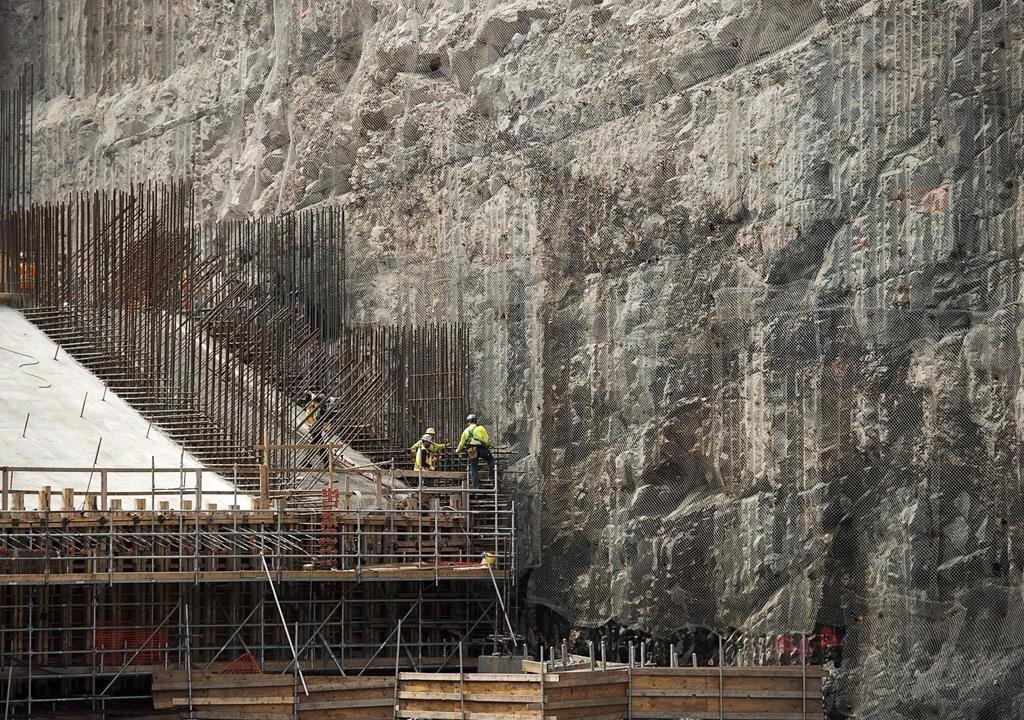

ST. JOHN’S, N.L.—The $12.7-billion Muskrat Falls hydroelectric dam in Labrador is finally nearing completion, billions of dollars over budget and years behind schedule.

But as the public is offered a final say at inquiry hearings Tuesday night in St. John’s and Aug. 8 in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, the province is still answering for a missed deadline on work intended to lessen the impact of methylmercury pollution on crucial food sources for downstream communities.