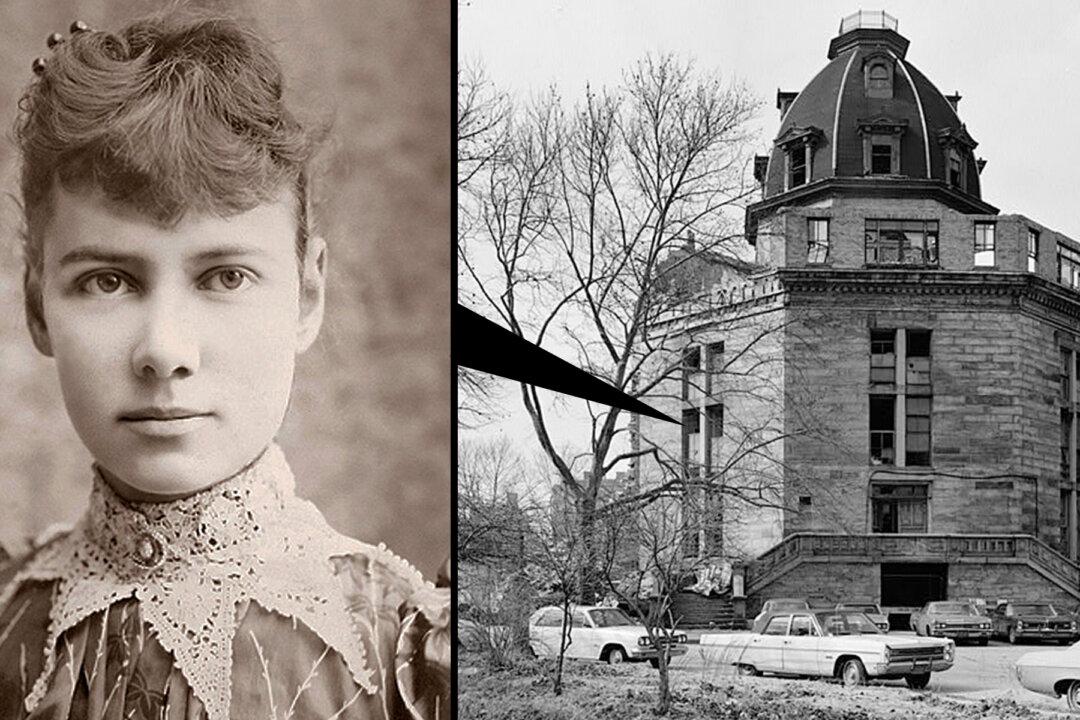

Elizabeth Cochran Seaman was a little before your time, but her legacy has changed the world we live in. She was born on May 5, 1864, in Pittsburgh, and you may know her by her pen name: Nellie Bly.

“Nellie” once spent 10 days in a women’s mental institution, all in the name of epic journalism.