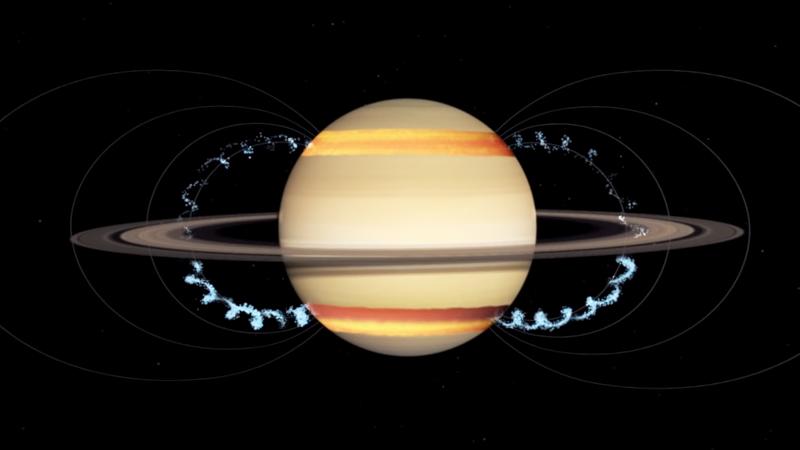

Whilst very few of us will be lucky enough to live for the next 100 million years, that’s how long Saturn’s rings have left before they vanish out of all existence.

Does that sound like a long time? Well, compare it to the previous estimate of 300 million years and it doesn’t take long to see that there’s a problem. Saturn is losing its rings!