WASHINGTON—The recent influx of unaccompanied children crossing the U.S. southwest border illegally has called attention to U.S. immigration courts. Can they handle the surge of cases? With the enormous political pressure to turn the immigrants back, should we be concerned that due process will be compromised?

Two federal immigration judges say their court system, which is administered by the Department of Justice (DOJ), is dysfunctional and badly in need of reform. Because immigration courts are housed in the Executive Branch, these courts do not operate as an independent court system. Immigration judges often lack the authority commonplace in a normal courtroom. Their legal standing is not even that of a judge, but rather than of an attorney working in the DOJ.

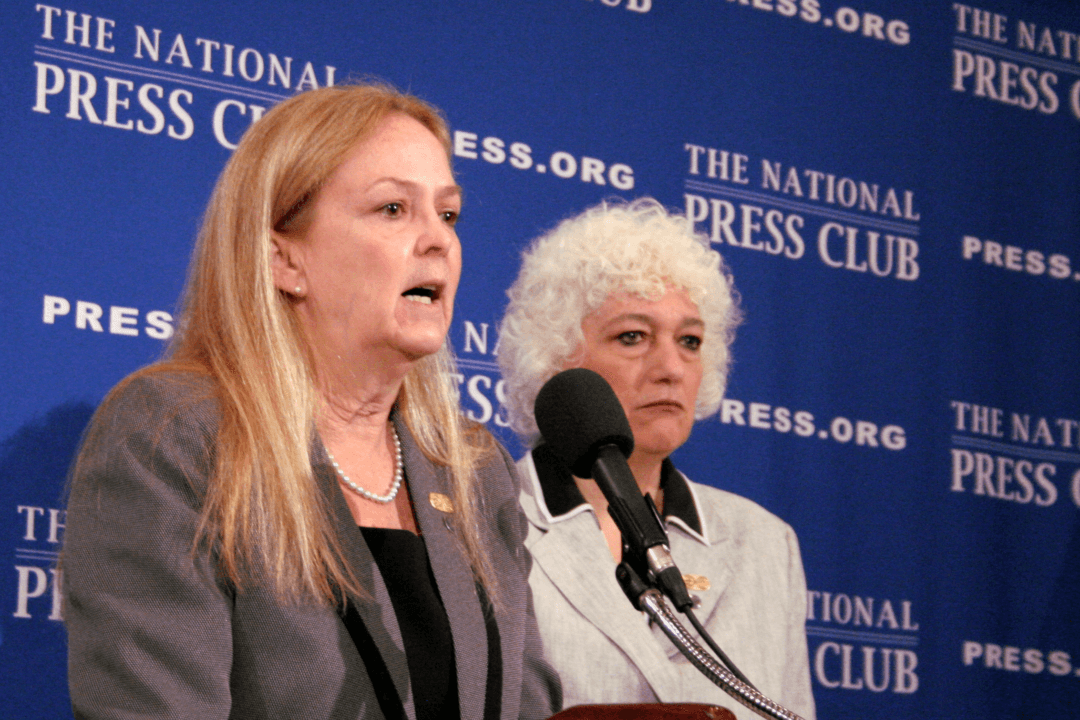

Judge Dana Leigh Marks, a federal administrative judge in San Francisco, and Judge Denise Noonan Slavin, a Miami-based administrative judge who hears cases in a federal detention center, held a news conference for press only, Aug. 27, at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C.

Both judges hold top offices at the National Association of Immigration Judges, and spoke as officers of NAIJ, and not as representatives of the DOJ or the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR).

The surge of unaccompanied children crossing the border has awaken public awareness to the stress on the immigration courts. It has given these two judges the opening for which they have been waiting to make their case in the public arena. The present crisis has highlighted the structural inadequacies of the immigration court system and its severe underfunding, they said. These shortcomings can best be remedied, they said, by establishing an independent immigration court system under Article One of the U.S. Constitution.

The border wall between the U.S. and Mexico in Nogales, Ariz., on July 6, 2012. Some say the funding for law enforcement is disproportionately higher than for the judicial process when it comes to immigration. (Sandy Huffaker/Getty Images)

Judicial Irregularities

Judge Slavin, who has been an administrative judge for 20 years, said that in the regulations of the DOJ, she and her colleagues are not judges, but “attorneys representing the United States government,” which produces a conflict of interest in their courtrooms.

“How can we expect to [be an independent arbitrator], if we are attorneys representing the same government as one of the parties that appears before us?” she asked.

Slavin cited several practices that would not be tolerated in a normal U.S. court system. Immigration judges cannot hold an attorney before them in contempt even though Congress provided that authority in 1996. The DOJ refuses to accept the will of Congress and enact the regulations needed. It won’t allow its judges, whom it views as only attorneys, to sanction other government attorneys from the Department of Homeland Security who appear in their courtrooms.

Whether an immigration judge recluses himself or herself due to a conflict of interest depends on the DOJ. It is not ultimately decided by the judge, which is how it is done elsewhere.

The change in priorities brought about by the border surge is another example of the political process interfering with the discretion of the judge and the responsible operation of the courts, Slavin said.

“There is no other court that would turn the docket on its head at the request of one party, but the immigration court is flipping the docket by moving cases to the front of the docket at the demand of Department of Homeland Security,” she said.

It doesn’t make any sense to hear a child’s case first if the child is coming here to be with his parents who are already in the court’s docket, Slavin said. The judge should be able to prioritize cases on a case-by-case basis.

Marks said that it’s a mistake to bring child cases to the front of the docket, because children need more time for the court to gain their trust and confidence. She said that international and domestic law recognize that children are different. “They are a vulnerable population that needs special protection,” she said. They need to be reunited with family members and a responsible adult to acquire counsel.

The NAIJ strongly encourages that those before the court have attorney representation, said Marks; it makes the cases better prepared and serves as a positive factor for all involved in the case, including prosecutors. But because removal proceedings are civil in nature, there is no right to an attorney. “Last fiscal year, over 40 percent were unrepresented,” Marks said.

Cases Delayed Years

Judge Marks, who has served as an administrative judge for 23 years, said the immigration courts are a low priority in the DOJ.

“Our role is to serve as a neutral court, but paradoxically we are housed in a law enforcement agency. Because we have been left to the mercy of the political winds that constantly buffet immigration issues, we have been resource-starved for decades,” she said.

Marks said that the immigration courts receive just 1.7 percent of the $18 billion annually allocated to immigration law enforcement, which she says is “clearly inadequate, and the strain is showing.”

Judge Slavin said the immigration courts have the status of Cinderella, receiving whatever is left over after the programs that “Justice considers more important are funded. As a result, instead of hearing cases within the first few months of someone crossing the border illegally, cases are delayed for years.”

Thus, those who are not entitled to be here become enmeshed in our communities, and those who are able to obtain legal status, remain in limbo for years.

Marks said that immigration law enforcement must “not be allowed to overshadow or control the immigration judicial process as it has in years past.”

Caseload

The two judges said that the number of judges needed for the caseload should be at least doubled.

Judge Marks, who has served as an administrative judge for 23 years, said, “There are 227 field immigration judges located around the country, handling dockets that currently exceed 375,000 cases.”

Marks said that because caseloads are not evenly distributed, she and other judges have several hundred more cases than average. With over 2,400 cases pending, she said, “It takes 15 months for the first arraignment-type hearing in my courtroom. After that, anywhere from three and a half to four years before the merits hearing is held.”

Court Inefficiencies

Marks and Slavin freely admit it will cost more money—at least upfront—and it will take an act of Congress to make the immigration courts judicially independent. They predicted, though, that the improvement would make the courts financially more cost-effective. When a case is decided without undue delays and the respondents feel they are being treated fairly, the need for reconsideration vanishes, Marks said.

“It is cheaper to resolve these cases at the trial court immigration level, rather than clogging our appellate courts. Our current system makes these expensive outcomes almost inevitable and the cost far more than it should [be].”

Slavin agreed, “If you try to streamline children cases at the border, and ... the less due process you get at lower levels, it’s going to translate in appeals and overwhelm the federal court system up at the higher levels.”

Judge Slavin said that all law-related organizations that have looked at their proposal, have endorsed it, including the American Bar Association, the Federal Bar Association, the Judicature Society, the National Association of Women Judges, and the American Immigration Lawyers Association.