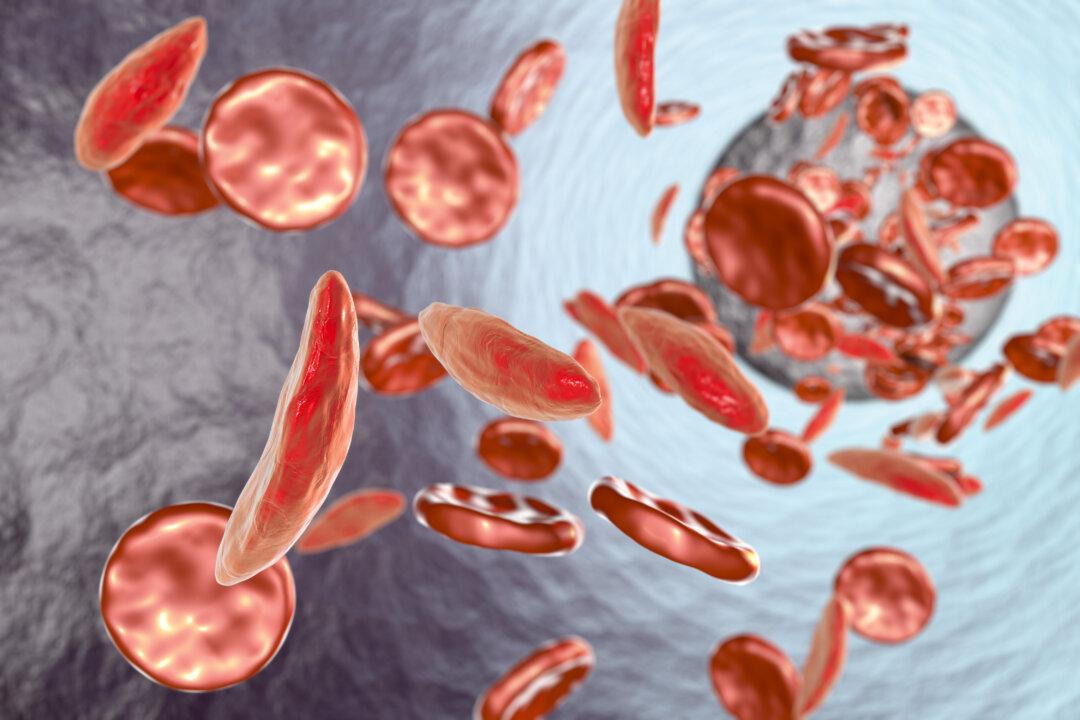

A study published in The Lancet brings to light an alarming reality: the global mortality burden of sickle cell disease is nearly 11 times higher than previously recorded.

The comprehensive report analyzes sickle cell disease, highlighting its prevalence and death rates from 2000 to 2021 across 204 countries. It reveals a significant surge in individuals battling this illness. This situation is worsened by cases slipping under the radar due to underdiagnosis and a lack of comprehensive knowledge about the disease’s overarching effects on global health.