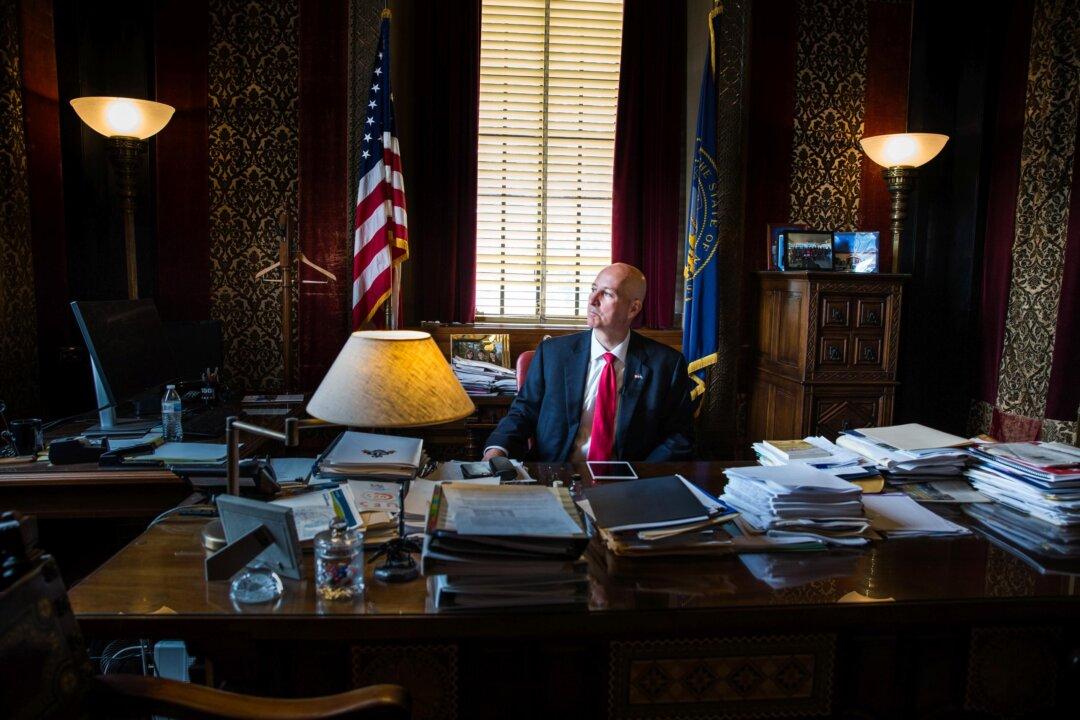

Steering the flagship farming state of Nebraska, Gov. Pete Ricketts has been all about opening doors for the world’s markets to access his state’s plentiful produce. From top-quality beef raised on the lush Great Plains pastures to the premier agri-tech that assists the growing of crops around the world, Nebraska has been exporting billions of dollars worth of products, a lot of it to East Asia.

It made perfect sense to Ricketts to lead a trade mission to China in 2016 in an effort to expand the market further yet.