“Organ Procurement and Extrajudicial Execution in China: A Review of the Evidence” by researcher Matthew Robertson was introduced on March 10 at a forum in Washington. It argues that there has been a polarization among approaches to the subject of organ harvesting in China.

On the one hand, international medical bodies have focused on bringing China into the international system of transplantation. Meanwhile, NGOs, activists, scholars, and private investigators have concentrated on the question of whether prisoners of conscience and other non-death-row prisoners are being killed for their organs.

One group argues for inclusion, the other for sanctions and moratoria.

Meanwhile, international human rights organizations have, for a variety of reasons, mostly not engaged on the topic. The main media outlets and academic studies of China have remained silent.

Amid this state of affairs, “Western governments have been confronted by two sharply divergent sets of messaging and have been unequipped and unprepared to adjudicate between them,” Robertson said.

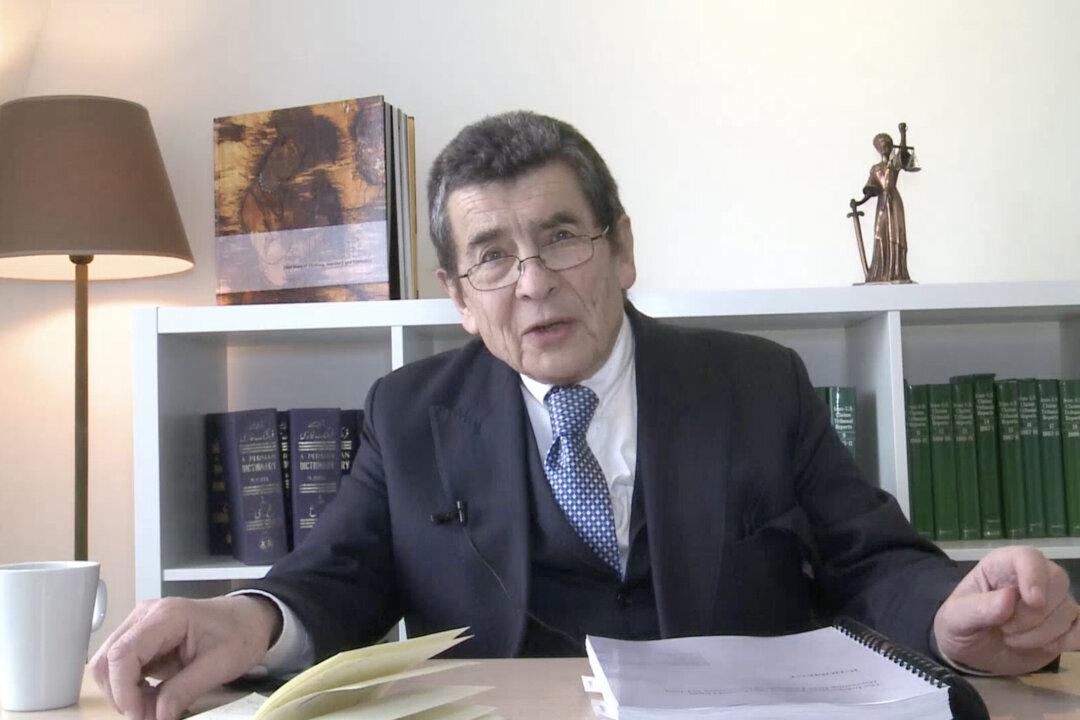

Robertson’s report seeks to loosen this logjam by reviewing the evidence, taking advantage of the fact that “the volume of quality evidence and the sophistication with which it can be analyzed has grown significantly” since the allegations were first made.

His review of the evidence, however, is more than just an analysis, as Robertson adds a “significant volume of new evidence” drawn from Chinese primary materials.

At the same time, Robertson seeks to respond to the strongest versions of “the concerns, doubts, and counterarguments raised” about the claims of forced organ harvesting from innocents.

In sum, this report marshals what is known and seeks to use this knowledge to persuade—to gain a hearing for the claims Robertson sets forth, and in doing so, ensure that “the burden of response should now be far greater.”

Tribunal

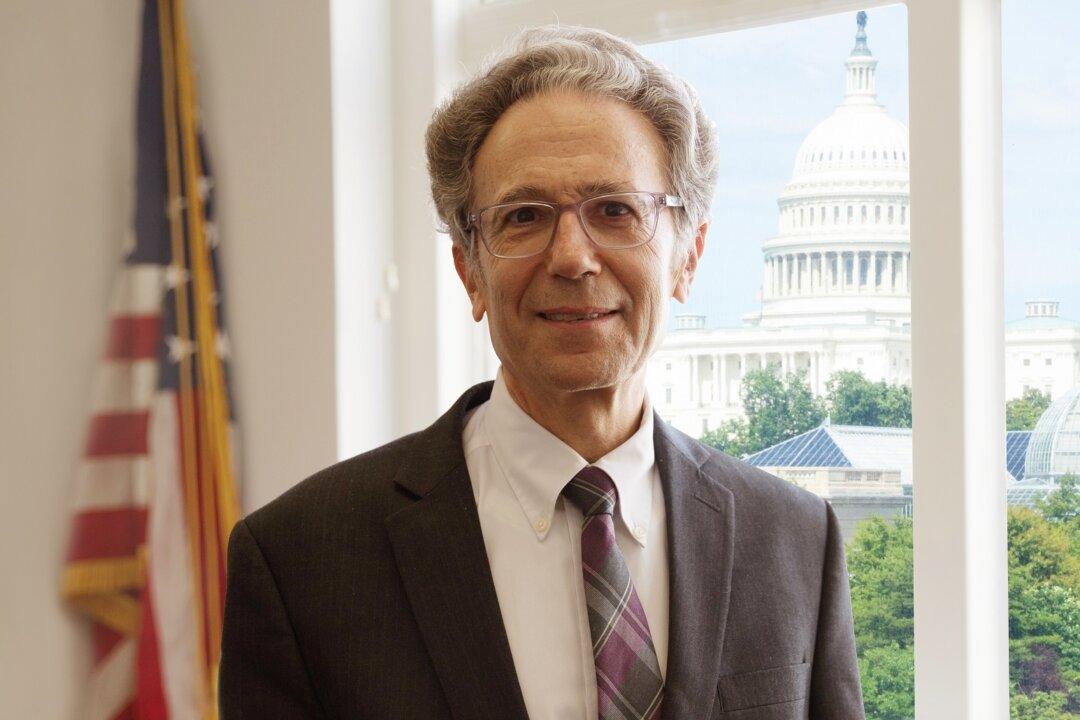

The first speaker at the forum, attending via a video, was Sir Geoffrey Nice QC of the United Kingdom, who led the Independent Tribunal into Forced Organ Harvesting from Prisoners of Conscience in China. That tribunal released its final report on March 1.Nice, who led the prosecution of Yugoslavia’s Slobodan Milosevic for war crimes, stated that “any person or organization that interacts in any substantial way with the People’s Republic of China” should recognize that “they are interacting with a criminal state.”

Complementary

Robertson’s report complements and supports the tribunal’s efforts, which also sought to address a failure to address the allegations of forced organ harvesting.There was “a question that needs to be answered, but it isn’t being answered for some reason,” Nice said.

That central question was whether or not China has been engaging in a wholesale industry of forced organ donations from both living and deceased prisoners, from which it then has made huge profits from domestic, as well as foreign, patients needing transplants.

The question of whether criminal offenses related to organ donation and transplantation in China had happened has been in the public forum for a long time, Nice said.

The International Coalition to End Transplant Abuse in China (ETAC), an Australian NGO, first approached Nice in 2016 and then other potential tribunal members to form an independent group to determine China’s culpability in the forced organ trade.

Nice saw that there are “certain advantages” in a “people’s tribunal.”

First, he said, “it can be composed of people who have no personal interest” in the matter at hand. “We are completely unpaid,” he said, “so there is no way we could lose our independence.”

ETAC said that there had been significant controversy over the claims against China. They approached Nice in December 2017 to form a group that would hear all the evidence, toward determining whether international crimes had been committed.

Nice “made sure there was a clear division between them and us,” ETAC Executive Director Susie Hughes said.

When the report and judgment were ready to be announced, “we didn’t know the result until 24 hours in advance,” she said.

Nice said, “The conclusion is obvious.” Forced organ transplantation has been happening on a significant scale since 1999, and the principal victims have been practitioners of the spiritual discipline Falun Gong, the report says. Uyghurs, an ethnic Turkic people who primarily live in northwest China’s Xinjiang Province, have also been victimized.

Explosion in Activity

In his remarks, Robertson outlined some of the compelling evidence that points to forced organ harvesting from prisoners of conscience, including the increase in transplantation after the Chinese regime began persecuting Falun Gong in 1999.“The number of liver transplants performed on an emergency basis ... or on demand expanded significantly post-2000,” Robertson said. “This is an extremely strong indication of a blood-typed pool of living donors able to be executed on demand.”

“In the year 2000, the transplant system basically exploded in activity,” Robertson said. “Thousands of doctors and nurses were trained. The number of hospitals that were doing transplants went from less than 199 to up to 1,000 by 2000.”

“And yet, through the 2000 period, the death penalty is going down. ... And then you look at other possible prisoner populations. ... So, for example, the evidence is consistent with organ harvesting of Falun Gong, blood tests in detention, including repeated blood tests. That’s very consistent with ... cross-matching ... with the potential recipient’s blood.”

In other words, living people are being pre-qualified as donors to needy recipients for life-saving kidneys, hearts, livers, and lungs.

The tribunal report cites a conversation with a spokesperson at a Beijing hospital, who said that “surgery can be arranged within one or two weeks.”

It goes on to say: “Such waiting times are not compatible with conventional transplant practice and cannot be explained by good fortune. Predetermining the availability of an organ for transplant is impossible in any system depending on voluntary organ donation. Such short-time availability could only occur if there was a bank of potential living donors who could be sacrificed to order.”

Hearings in US Congress Since 1996

The forum heard statements from several experts in the field, including Rep. Chris Smith, a Republican from New Jersey.Noting that the tribunal in which Nice had led the prosecution against Milosevic had become “a model for holding bad players to account,” Smith told the audience, “In 1996, I chaired the first congressional hearing ever on human rights abuses and organ harvesting in China.”

That hearing was bolstered by the evidence of two Chinese doctors “who came here and who didn’t go back, thank God,” Smith said.

Indeed, the record of that hearing shows that Dr. Qian Xiaojiang, a former doctor in Anhui Province, concluded his testimony by saying: “To conclude, I believe that without the use of organs from executed prisoners, over 90 percent of China’s transplant surgeries would be unthinkable. Traditional Chinese conceptions preclude people from donating part of their bodies.”

Twenty-four years ago, Smith’s hearing focused on the organ-transplant industry as supplied by executed prisoners.

Today’s organ atrocities focus on prisoners of conscience, particularly those who practice Falun Gong (also known as Falun Dafa), a spiritual discipline that involves meditative exercises and teachings based on truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance.

Forced organ donations are also said to have been committed among the Uyghur population, who have been subjected to forced internment and re-education in recent years.

Following the Chinese Communist Party’s ban of Falun Gong in 1999, harsh and inhumane measures were taken—extrajudicially—to force adherents to renounce both their beliefs as well as their practice of Falun Gong exercises.

Chinese human rights activist Yu Ming, who arrived in the United States last year, gave an account of the abuses he was subjected to while in prison and labor camps.

In secretly recorded video footage, in which he played the role of a patient needing a transplant, he documented conversations with Chinese doctors and medical staff who quoted prices and, most importantly, very short wait times for various organs.

In one clip, the doctor asks repeatedly, “You’re not a journalist, are you?”

Time to Act

Louisa Greve, director of global advocacy for the Uyghur Human Rights Project, asked if there should be a ban on exchanges and training conferences with transplant doctors from China.“We need to think about the policy responses we need to be working on,” Greve said.

Robertson offered a call to arms in his conclusion to his report.

“As far as elite opinion is concerned—that is, in human rights organizations, the China field, the medical community, the executive branches of Western governments, and the major media corporations—these allegations could happily remain in limbo,” he said.

“We urge observers to examine the evidence ... consider our suggestions, reflect on the ethical justification for doing so, and act.”