Focus

Wildlife Conservation

LATEST

Historic California Condor Season of 17 New Chicks Reported by Los Angeles Zoo

The species is the largest land bird in North America with wings spanning nine-and-a-half feet. Zoo visitors can view the birds daily, except Tuesday.

|

Leonardo DiCaprio Calls for End to Tasmania’s Forest Logging Before Election

‘Our planet’s last remaining giants are in danger,’ the actor said.

|

Leonardo DiCaprio Puts Swift Parrot Conservation Into Global Spotlight

‘Leonardo DiCaprio has put Tasmania on the map big time, and the plight of the swift parrot is now well and truly global,” former Greens leader said.

|

A Call for Saving Leviathan, for Saving the Whales

Is humanity capable of saving the seas? The ways the seas and the whales go, so does civilization. The seas are acidifying. Whales are key not just for their fecundation of the phytoplankton on which we depend for oxygen, but also for the entire immune system of the oceans.

|

The Last Polar Bears

We first went to Churchill, Canada, to see its famous polar bears, whose life was being threatened by the vagaries of a civilization. We went to touch the space of their frontier, because we knew that their continued presence on earth represents a critical buoy to our future.

|

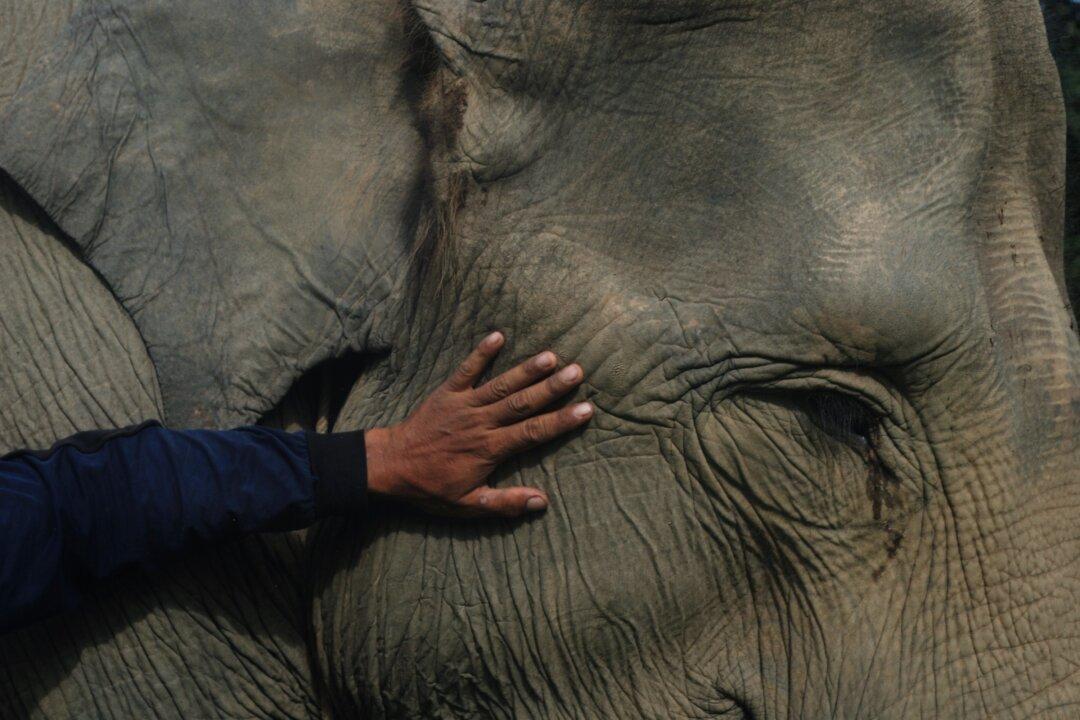

The Colossus of Existence: Why the Elephant Is Invaluable

A world without elephants, even a world with severely reduced populations only incites more violence and convulsions across the entire body of the African and Asian continent.

|

A Bluebird Is Stalking Me

Bluebird populations crashed in the 20th century by 90 percent. But people put up nesting boxes around the country, and now they are staging a comeback

|

The Return of the Black Bears

With no natural predators or pressure from humans, black bears have made a precipitous comeback in the past few decades.

|

Can Zoos Save the World?

Today, many zoos promote the protection of biodiversity as a significant part of their mission. As conservation “arks” for endangered species and, increasingly, as leaders in field conservation projects such as the reintroduction of captive-born animals to the wild, they’re preparing to play an even more significant role in the effort to save species in this century.

|

Chopping Off the Rhino’s Horn and the War on Wildlife Crime

As the electric saw cuts into the base of the horn of the live rhino lying at my feet, I feel an uncomfortable guilt. The rhino shakes and judders and there is an unpleasant smell reminiscent of burning hair. I glance nervously at the friends around me, clad in khaki and camouflage.

|

5 Ways to Stop the World’s Wildlife Vanishing

Full marks to colleagues at the World Wildlife Fund and the Zoological Society of London for the “Living Planet Report 2014” and its headline message, which one hopes ought to shock the world out of its complacency: a 52 percent decline of wildlife populations in the past 40 years.

|

Caltrans Requests $2.5 Million in Funding for Mountain Lion Overpass

In California, Mountain lions have been struck and killed by cars, and inbreeding is threatening the population’s diversity.

|

Rarely Seen Whale Spotted Off Southern California Coast

Southern California has seen a surge in whales recently, most notably a tropical whale called Bryde’s whale.

|

Photos of Meerkats Because They’re Cute, Playful, Fun to Watch (Photo Gallery, +Video)

African wildlife photography at its most playful, the pint-sized meerkats treat the photographer like a big, strange-looking brother.

|

Historic California Condor Season of 17 New Chicks Reported by Los Angeles Zoo

The species is the largest land bird in North America with wings spanning nine-and-a-half feet. Zoo visitors can view the birds daily, except Tuesday.

|

Leonardo DiCaprio Calls for End to Tasmania’s Forest Logging Before Election

‘Our planet’s last remaining giants are in danger,’ the actor said.

|

Leonardo DiCaprio Puts Swift Parrot Conservation Into Global Spotlight

‘Leonardo DiCaprio has put Tasmania on the map big time, and the plight of the swift parrot is now well and truly global,” former Greens leader said.

|

A Call for Saving Leviathan, for Saving the Whales

Is humanity capable of saving the seas? The ways the seas and the whales go, so does civilization. The seas are acidifying. Whales are key not just for their fecundation of the phytoplankton on which we depend for oxygen, but also for the entire immune system of the oceans.

|

The Last Polar Bears

We first went to Churchill, Canada, to see its famous polar bears, whose life was being threatened by the vagaries of a civilization. We went to touch the space of their frontier, because we knew that their continued presence on earth represents a critical buoy to our future.

|

The Colossus of Existence: Why the Elephant Is Invaluable

A world without elephants, even a world with severely reduced populations only incites more violence and convulsions across the entire body of the African and Asian continent.

|

A Bluebird Is Stalking Me

Bluebird populations crashed in the 20th century by 90 percent. But people put up nesting boxes around the country, and now they are staging a comeback

|

The Return of the Black Bears

With no natural predators or pressure from humans, black bears have made a precipitous comeback in the past few decades.

|

Can Zoos Save the World?

Today, many zoos promote the protection of biodiversity as a significant part of their mission. As conservation “arks” for endangered species and, increasingly, as leaders in field conservation projects such as the reintroduction of captive-born animals to the wild, they’re preparing to play an even more significant role in the effort to save species in this century.

|

Chopping Off the Rhino’s Horn and the War on Wildlife Crime

As the electric saw cuts into the base of the horn of the live rhino lying at my feet, I feel an uncomfortable guilt. The rhino shakes and judders and there is an unpleasant smell reminiscent of burning hair. I glance nervously at the friends around me, clad in khaki and camouflage.

|

5 Ways to Stop the World’s Wildlife Vanishing

Full marks to colleagues at the World Wildlife Fund and the Zoological Society of London for the “Living Planet Report 2014” and its headline message, which one hopes ought to shock the world out of its complacency: a 52 percent decline of wildlife populations in the past 40 years.

|

Caltrans Requests $2.5 Million in Funding for Mountain Lion Overpass

In California, Mountain lions have been struck and killed by cars, and inbreeding is threatening the population’s diversity.

|

Rarely Seen Whale Spotted Off Southern California Coast

Southern California has seen a surge in whales recently, most notably a tropical whale called Bryde’s whale.

|

Photos of Meerkats Because They’re Cute, Playful, Fun to Watch (Photo Gallery, +Video)

African wildlife photography at its most playful, the pint-sized meerkats treat the photographer like a big, strange-looking brother.

|