Full marks to colleagues at the World Wildlife Fund and the Zoological Society of London for the “Living Planet Report 2014” and its headline message, which one hopes ought to shock the world out of its complacency: a 52 percent decline of wildlife populations in the past 40 years.

Over the summer I re-read Fairfield Osborne’s 1948 classic “Our Plundered Planet”—the first mass-readership environmental book that detailed the scale of the damage humanity wrought on nature. Faced with the figures in this report it is easy to slip into despondency and to blame others. But this would be a mistake. At the time, Osborne’s report must have been equally alarming, but the eclectic conservation movement of which he was part responded with confidence, hope, and vision.

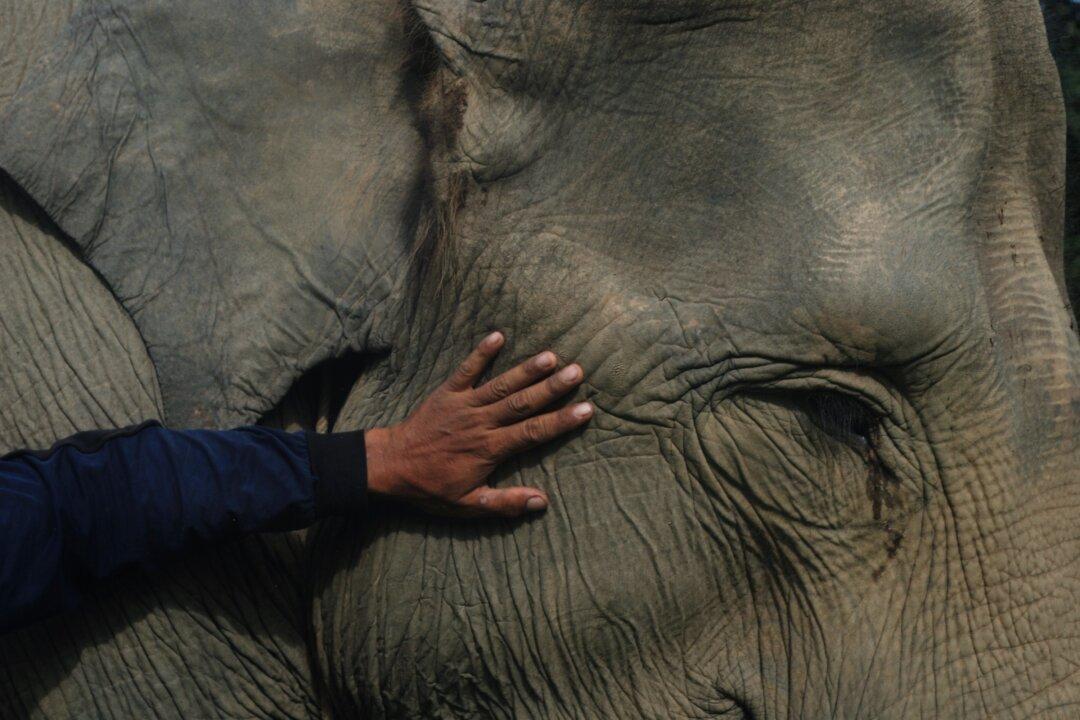

Their achievements were huge: the creation of a reserve network that forestalled the extinction of African creatures such as the elephant and rhino, the creation of a nature conservation agency, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) within the U.N., and a raft of international wildlife agreements.

Today, conservation-minded people will probably be wondering what can be done to reverse wildlife declines. For me the question is how can today’s conservationists leave a wildlife legacy for the 21st century, and I think there are five ways we can change conservation to better fit the circumstances we face.

1. Decentralize and Diversify

The effort to ensure that nature conservation became a policy area of the U.N. necessitated developing a strong international conservation regime. This has served us well, but the world has changed: centralized authority has given way to messy, networked governance organized across many levels.

If the Balinese want to restore Bali starling populations in coconut plantations I say applaud their vision and learn from their innovation. What matters is that wildlife populations flourish, not that some institutionalized notion of a “wild species” gains global consensus. It is time to nurture diversity in conservation practice.

2. View Wildlife as an Asset

Since the 1990s conservation has become overly technocratic, with nature framed as a natural resource and stock of capital available for human economic development. Given human self-interest this just leads to arguments over who gets what share.

I suggest a better way to frame environmental policy is in terms of natural assets—places, attributes, and processes that, while representing forms of value to invest in, are also at risk of being eroded and must be protected.

We’ve done this before—think of great national parks where wildlife conservation, natural beautification, and outdoor recreation combine for the benefit of wildlife, while also emphasizing regional or national identity, health, and cultural and economic worth.

3. Embrace Re-Wilding

Re-wilding is gaining traction. I see re-wilding as an opening, an opportunity for creative thinking and action that will affect the future. A key theme is restoration of trophic levels—in which the missing large animals at the top of the food chain are reintroduced, allowing natural ecosystem processes to reassert themselves.

We might ask whether today’s reported declines in wildlife are a symptom of the ecosystem becoming simpler and, if so, whether re-wilding will lead to more abundant wildlife. Ecological intuition suggests the latter but in truth we don’t know.

In my view we need large-scale, publicly financed re-wilding experiments to explore and develop new ways of rebuilding wildlife populations as an asset for society.

4. Harness New Technologies

It’s clear that wildlife conservation is moving from being a data-poor to a data-rich science. The methods that underpin the “Living Planet Report” are state-of-the art, but even so we have yet to capture the analytical potential of “big data.”

Recent rapid developments in sensor technologies look set to bring about a step change in environmental research and monitoring. In 10 year’s time, I predict that the challenge for indexing the planet will shift from searching out and compiling data sets to working out how to deal with an environmental “data deluge.”

Despite this, wildlife conservation lacks a coherent vision and strategy. There are plenty of interesting technological innovations, but they are fragmented and individualistic in nature. We need leadership and investment to better harness them.

5. Re-engage the Powerful

Like it or not, the wildlife conservation movement was at its most influential—as a policy and cultural imperative—when it was filled with active members drawn from the political, aristocratic, business, scientific, artistic, and bureaucratic elites.

This was between 1890 and 1970. Over the past 40 years conservation organizations have become more professional, building close working relations with bureaucrats, but approaching other elites simply as sources of patronage, funds, and publicity. Conservation organizations must open up, loosen their corporate structures, and let leaders from other walks of life actively contribute their opinions, insight, and influence to the cause.

But Above All, Keep Caring

These are five starting points for discussion rather than prescriptions. Perhaps the greatest asset we have is the deep-rooted sense of concern for wildlife found across cultures, professions, and classes. It’s time to open up the discussion, to put forward new ideas for debate, and to ask others to suggest new and novel ways to save wildlife.

Paul Jepson is the course director of Master of Science in Biodiversity, Conservation and Management at University of Oxford in the U.K. This article previously published at TheConversation.com.