Commentary

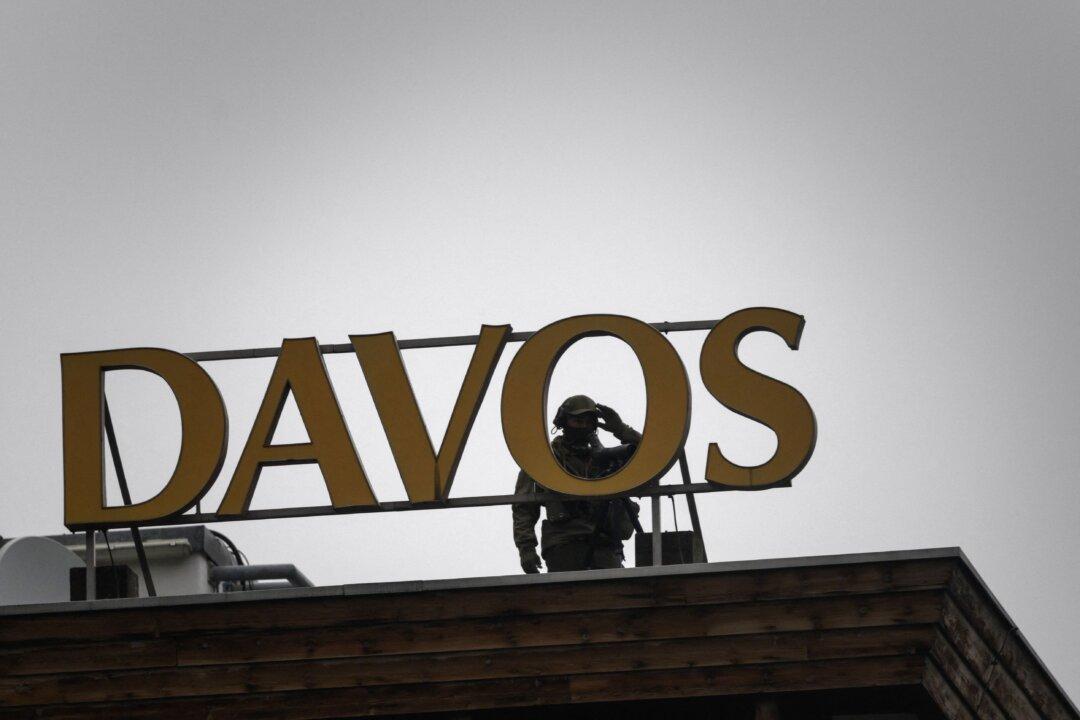

Are ordinary people served or threatened by globalization? The term itself, of course, means different things depending on who is using it. But the form of globalization that has provoked populist-oriented passions in both hemispheres in recent years has at its heart the determination to suppress people’s exercise of the powers of representative government.