Commentary

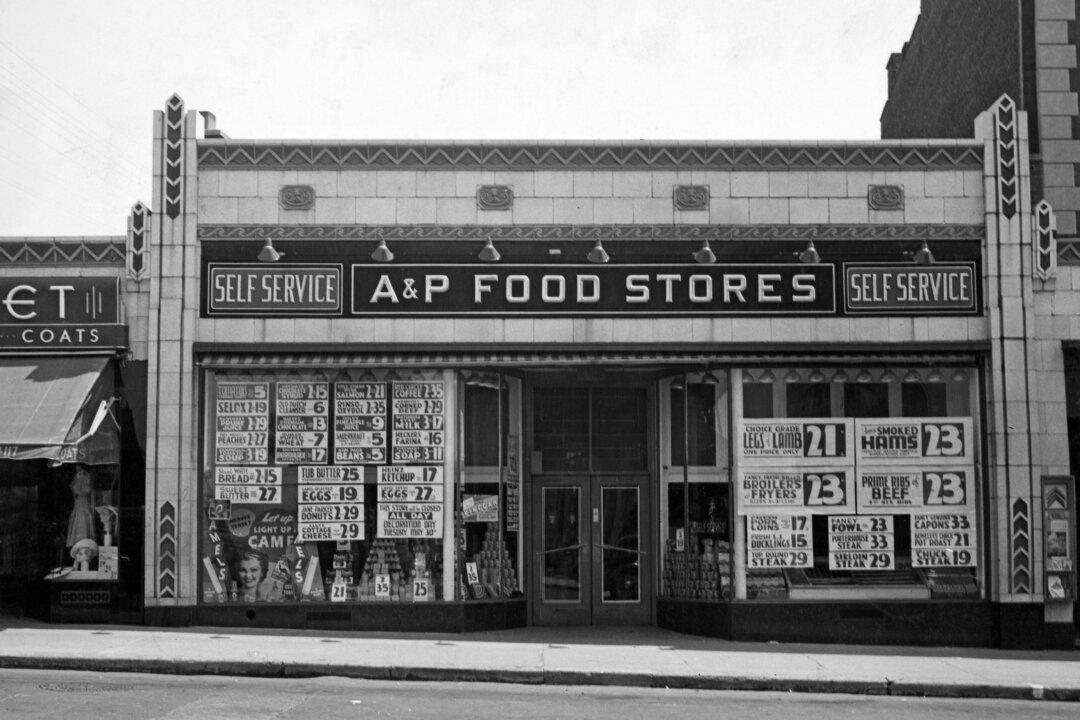

Walmart, which remains America’s largest employer despite Amazon’s rise to the status of world’s largest online seller, announced on May 14 that it will let go of hundreds of its corporate staff and require the majority of those of its 1.6 million employees working remotely to return to the office, some four years after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.