Commentary

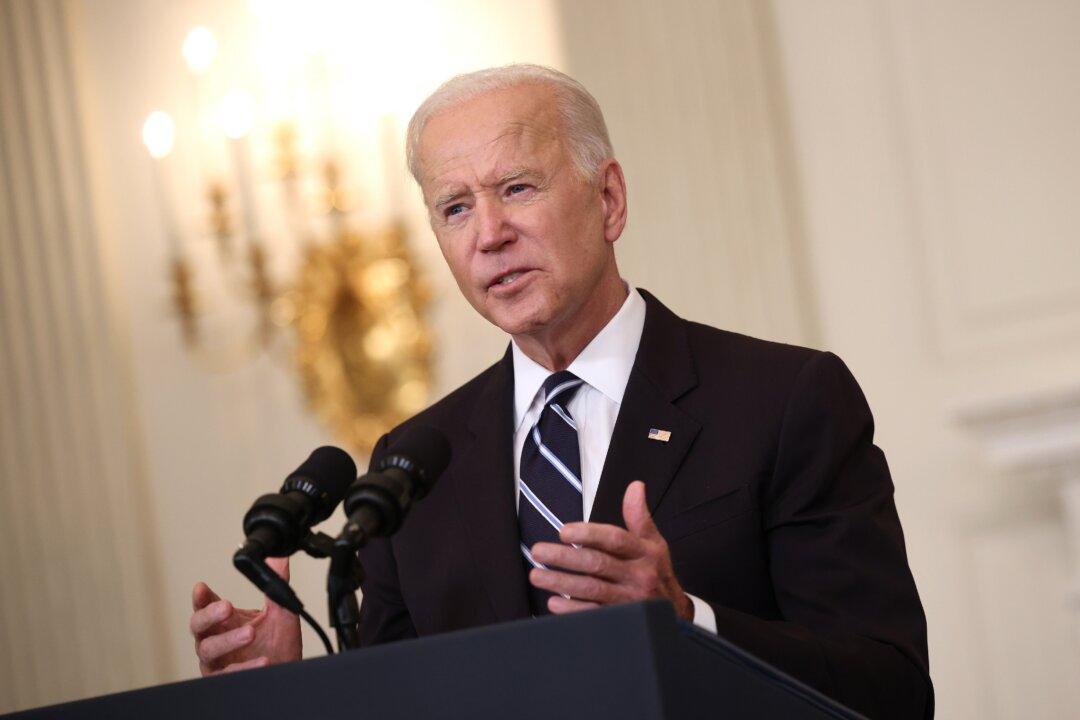

If former President Donald Trump wants to claim a legacy, he can at least point to China trade policy. The Biden administration just showed that it plans to remain true to Trump’s policies.

If former President Donald Trump wants to claim a legacy, he can at least point to China trade policy. The Biden administration just showed that it plans to remain true to Trump’s policies.