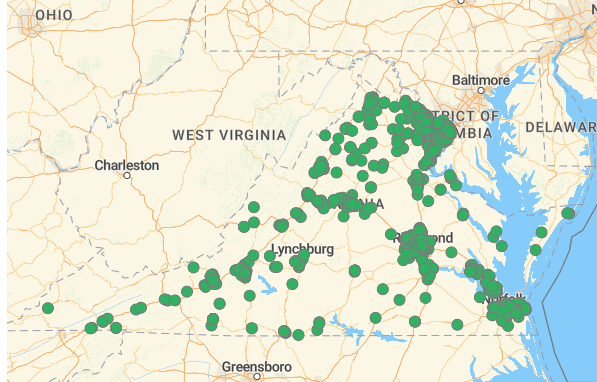

Since passing a Clean Car law similar to California’s, Virginia’s electrical vehicle (EV) sales have grown from 20,000 registered EVs to a little over 65,000. However, some people, including Virginia’s Republican lawmakers, don’t think the state can meet the upcoming EV sales goals and even more importantly, the law disregards the needs of rural consumers said a Virginia House Delegate.

“There’s a regional component, I’m from the rural area. This is not downtown Northern Virginia, Alexandria, … it’s a completely different model here that we live under. There’s a lot of people that push this legislation forward, [but] didn’t take that into consideration,” Wilt told The Epoch Times.