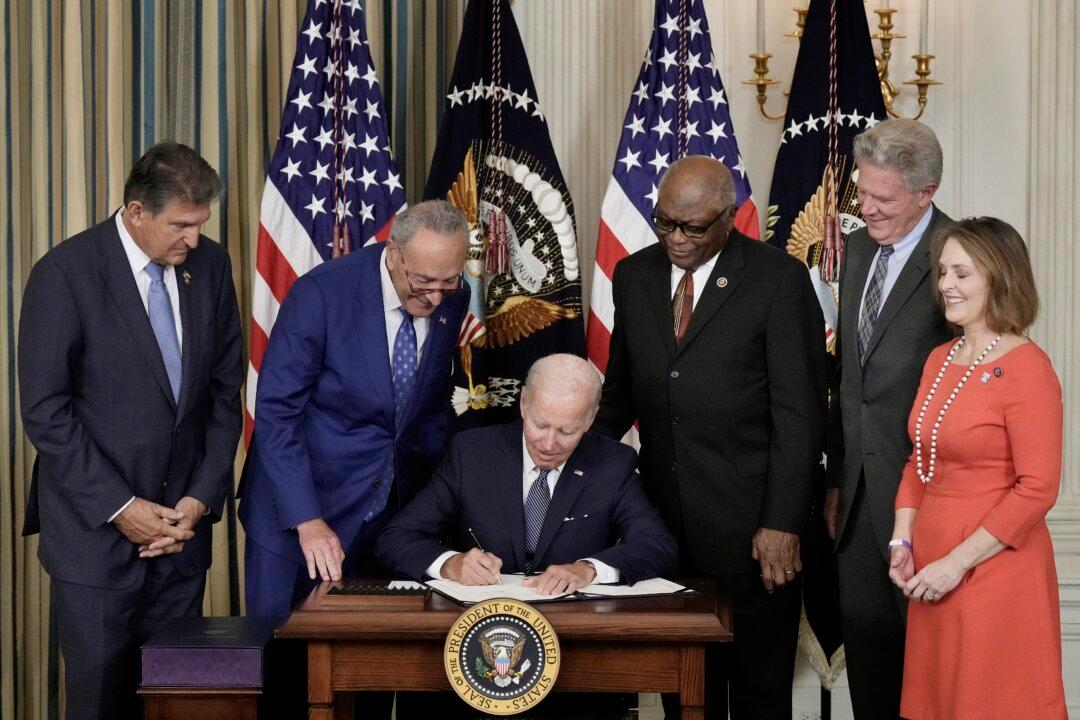

A corporate tax increase embedded in what critics are calling the “deceptively named” Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) could imperil as much as $8 billion a year in low-income housing funds, according to experts.

The low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC) is a dollar-for-dollar tax deduction introduced during the Reagan administration. It has helped create and rehabilitate millions of homes for low-income Americans. However, the IRA and its 15 percent minimum corporate tax rate could mean that corporations and the people who run them could reconsider their support if they get nothing to show for it, said E.J. Antoni, a Ph.D. in economics and a research fellow for regional economics with the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank.