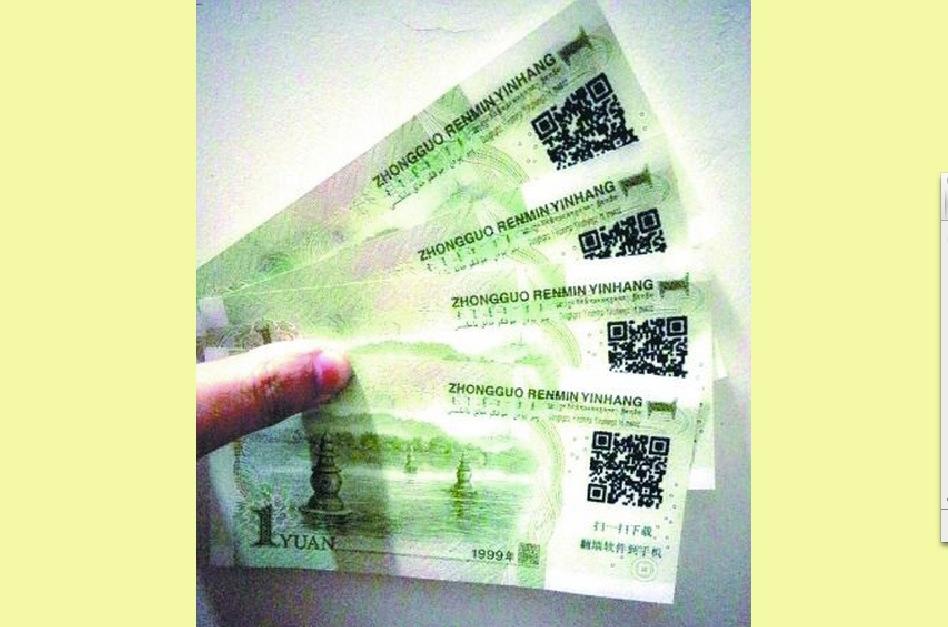

When shopping for groceries in a supermarket in Wuhan the other day, Mrs. Wu received for her change four one yuan notes, each with symbols on them that she had never seen before.

Underneath a black and white square of pixellated dots—which had evidently been stamped onto the note—were the words: “Scan and download software to break the Internet firewall.”

Wu took the bank notes to the Wuhan Evening News, and the story then went national. Even the Communist Party’s mouthpiece, the People’s Daily, reposted the article on its website.

In comments responding to the news articles, and in remarks made on Sina Weibo, a popular microblogging platform in China, users wrote about how they had themselves encountered notes with the symbols, called QR codes, on them.

The Codes

QR codes can be scanned, like a barcode scanner in a supermarket, by mobile devices. They then automatically take the user to a website. In this case, it goes to a Google short link that redirects to an Amazon cloud link, where a software file may be downloaded.

QR codes are not unusual, nor are efforts to circumvent the Internet blockade, but Chinese Internet users were fascinated by the way the matter was appearing in media across China: it was an admission that there is an Internet firewall in China and that there are established ways to get around it.

Most curious of all, perhaps, was the identity of the individuals who likely stamped the QR codes onto the money. Though there is no way of definitively proving who is responsible in this case, putting messages on money is a tactic long used by practitioners of Falun Gong, a traditional spiritual practice that has been persecuted in mainland China since 1999.

A screenshot shows that Party mouthpiece People’s Daily republished the report about QR codes for circumventing the Internet firewall being found on bank notes. (Screenshot/People’s Daily/Epoch Times)

Meeting a Need

Anyone, in fact, can download the QR codes from the website dongtaiwang.com, which belongs to Dynamic Internet Technology, a company that produces the Freegate circumvention software.

Typically, a website that hosted anti-censorship software would itself be censored. But Bill Xia, the president of Dynamic Internet Technology, said in a telephone interview that there are ways to disguise the URL at the time that its scanned, so that users can still access a page from which they can download the software to their smartphones. If the Chinese authorities wanted to block these links, they would probably have to cut off access to Amazon Web Services, where the files are stored. Blocking Amazon in China could have serious business ramifications.

He said that it only works on Android and PC operating systems at this stage.

“We found this usage of the QR codes interesting,” Xia said. “We did get input from China, user feedback that we should provide QR codes so they can distribute them in China,” he said. “It’s interesting to see that it’s actually happening and see the news get publicized.”

The reports in China did not indicate that practitioners of Falun Gong may have been behind the effort to stamp the notes. The report identified the code as an “advertisement,” and warned readers “never to try scan it.”

But netizens seemed unswayed. Many left their sentiments in the comments sections of popular websites. “I often see Falun Dafa words [printed on money],” said netizen yubos1. Another remarked: “Whoever has seen one yuan bills with words stamped on it will understand what the code is about.”

Another user, woaixuneng520, wrote: “I tried to scan it. Oh my! I can finally watch YouTube.”

Some were disappointed with the blurry photographs that the newspapers published of the bank notes with the codes on them. “Can’t the reporter take a clearer picture? I scanned my screen for so long,” one user said.

“It’s so useful,” wrote Qingwenwoding. “Only when you break through the firewall can you see China clearly.”

Those Who Stamp

Soon after the persecution of Falun Gong started in 1999, practitioners of the discipline began using a variety of nonviolent ways to inform the Chinese people about it. The regime has attempted to shut down independent information about both the practice and the persecution, while also spreading anti-Falun Gong propaganda to justify their actions. The use of QR codes on banknotes—or posted onto telephone poles on the street—is the latest development in this strategy.

Hu Ping, the chief editor of Beijing Spring, a pro-democracy magazine, said in a telephone interview: “We all know that Falun Gong has contributed a lot in developing circumvention software, which has helped break the Internet blockade. The recent reports, especially in official media, will obviously expand the profile of Falun Gong in China.”

Hu added that, given that the persecution of the practice was highly contentious even inside the Communist Party, and was one of the pet projects of the political foes of current leader Xi Jinping, the appearance of these news articles may be a kind of warning to that faction—which includes the recently troubled security czar Zhou Yongkang and former regime leader Jiang Zemin—not to attempt a political comeback.