Originally founded under Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership in 2001 and holding its first meeting in 2002, the nonprofit organization was incorporated with 26 other Asian countries.

Its stated mission at its founding, “promoting economic integration in Asia,” has evolved into “pooling positive energy for the development of Asia and the world.”

This year’s theme is titled “The World in COVID-19 and Beyond: Working Together for Global Development and Shared Future.”

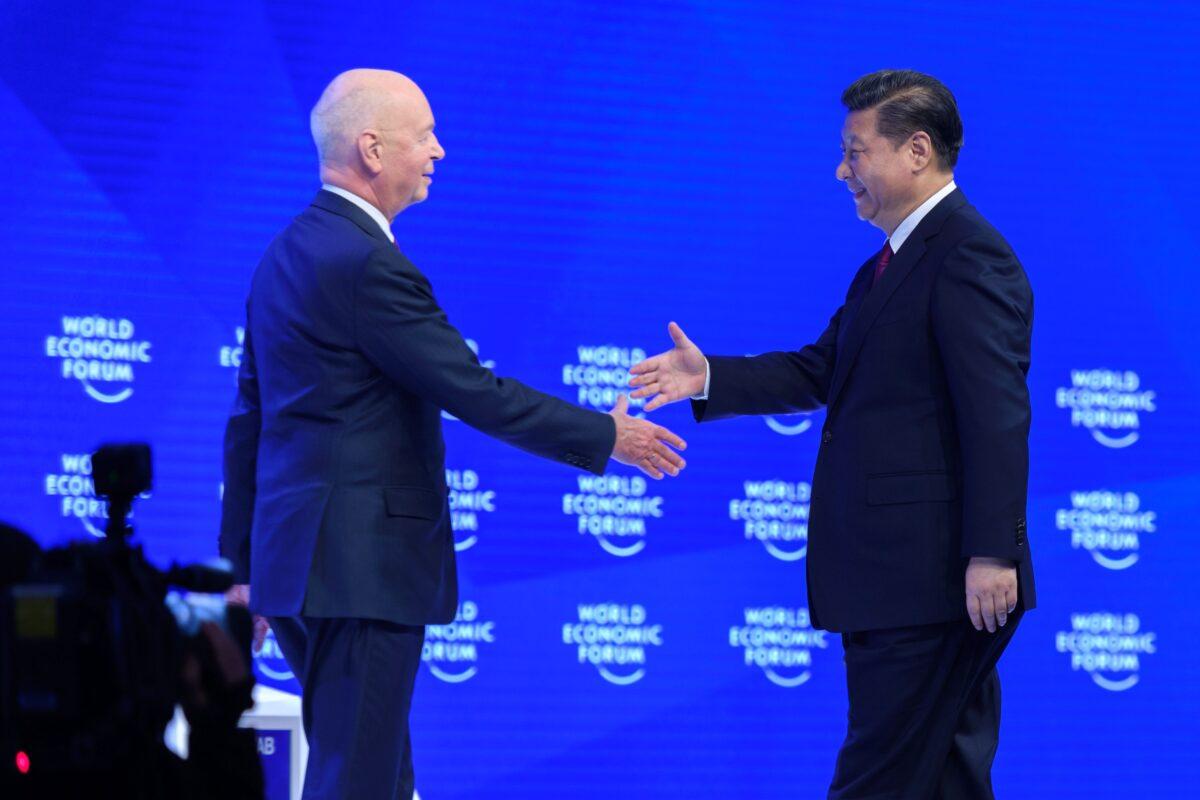

If this sounds a lot like the annual Davos Summit of the World Economic Forum (WEF), that’s because it’s essentially the same concept. BFA is commonly referred to as the “Asian Davos” and is openly modeled on the WEF.

This year’s WEF theme is at least superficially more innocuous than in previous years: “Working Together, Restoring Trust.” WEF founder and Executive Chairman Klaus Schwab has apparently realized that titling his exclusive gatherings after global schemes befitting a James Bond villain isn’t conducive to the elite agenda.

Still, one imagines that it must come as a disappointment for those WEF attendees who rather enjoy the condescending shroud of mystery (and a hint of conspiracy) that their meetings conjure up among us commoners.

Every BFA seminar, including those previously mentioned, features at least one prominent member of the Chinese government, business, or academia. That equates to CCP representation, if not outright leadership, on each panel.

Additionally, the panels are also moderated by media or government representatives of the CCP. This ostensibly ensures that the conversation proceeds in a manner that is either explicitly favorable to the Party or actively steers away from any subject that could cast a potentially less-than-positive light on it.

Curating the image of the CCP and promoting its policies is the actual underlying theme of the entire BFA conference. As if there were any questions about this fact, seminars such as “The Belt and Road: A New Practice of Cooperative Development” (referring to China’s predatory economic investment project, the Belt and Road Initiative) explicitly confirm it.

This isn’t to say the BFA is any more malicious than the WEF. The central focus of both meetings revolves around the need for greater centralized control to account for global problems that transcend national borders. This usually involves delegating policy decision-making to unelected bodies insulated from any actual accountability over their decisions.

In this way, the BFA and the WEF are similar. But whereas the latter seeks to co-opt the CCP as a tool to help it consolidate its reach and influence, the former explicitly acknowledges the CCP’s leading role.

This is an important distinction. The CCP has no risk of actually being controlled by the WEF, but the CCP can utilize the WEF to gain increased relative geopolitical clout for China. The CCP knows what disconnected elites in Brussels and Davos want to hear. As such, China wins favor with language about diversity, equity, and carbon-neutrality while being one of the least diverse or equitable regimes in the world, all the while continuing its construction of coal-fired power plants unabated.

Chinese leader Xi Jinping may talk about globalization, interconnectedness, and the need for greater cooperation with partner countries at Davos, but make no mistake about it—at Boao, the CCP is in charge of the show.

Still, this may not actually provide a moral qualm for Western attendees of either summit. Whatever they may be, they are certainly not dumb. Therefore, they must know that China is only superficially committing to abstract moralizing about cooperative goals while pursuing only its national interest.

Meanwhile, Beijing will continue to pursue a policy that is only beneficial for the consolidation of the CCP and the relative weakening of the West. As such, the task of investigating the dynamic between BFA and WEF can provide a useful microcosm for understanding the relationship between the CCP and Western elites in general.