U.S. Ambassador to China Terry Branstad will step down from his post in early October, ending a three-year tenure in Beijing marked by deteriorating relations between the two countries.

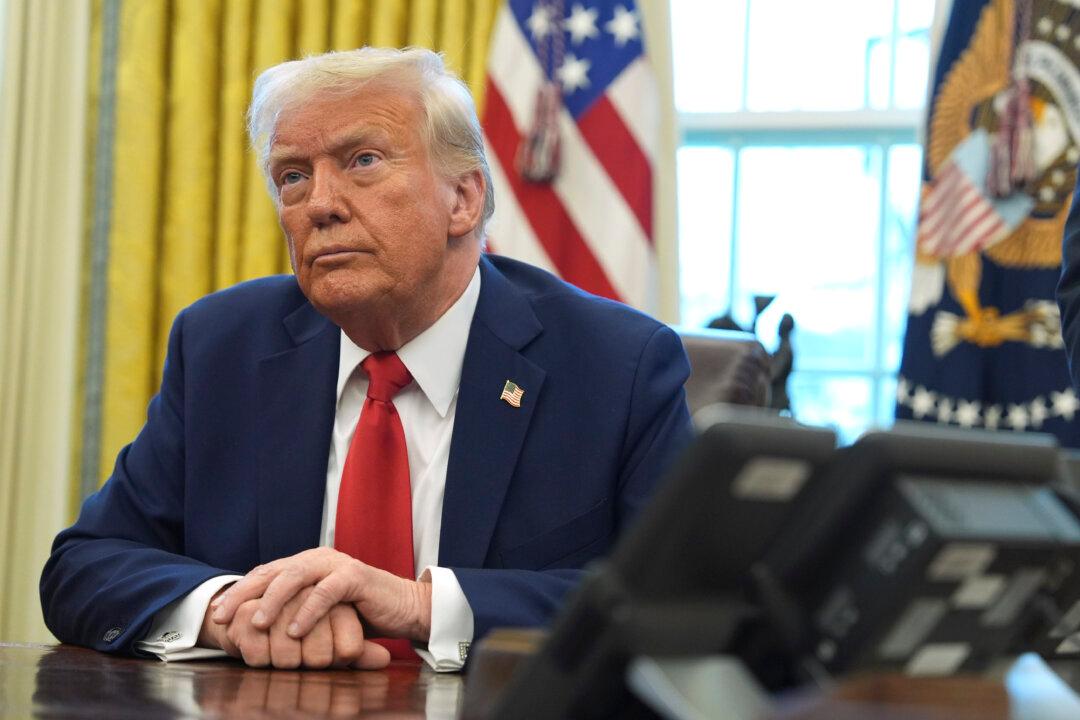

Branstad, who was appointed by President Donald Trump in 2017, informed the president of his decision in a phone call last week, the U.S. Embassy said in a statement on Sept. 14. It didn’t provide the reason for his departure.