News Analysis

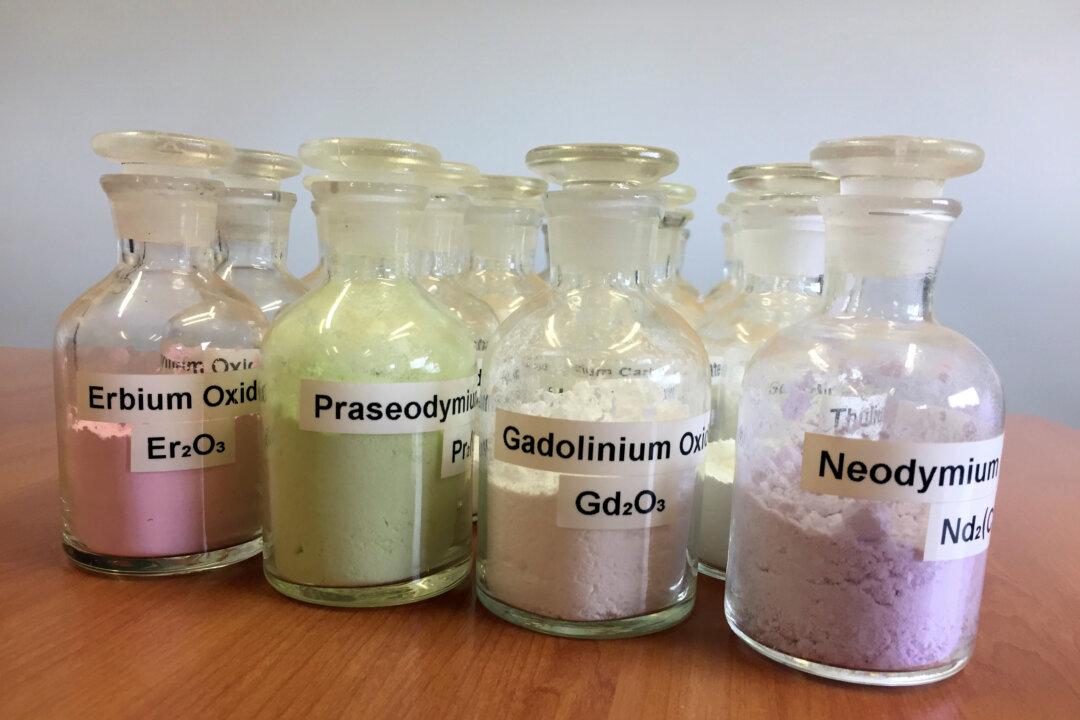

The battle for control of the global rare earths supply chain is heating up, with the U.S. Department of Defense investing in a new processing plant in a bid to challenge China’s chokehold over the critical minerals.

The battle for control of the global rare earths supply chain is heating up, with the U.S. Department of Defense investing in a new processing plant in a bid to challenge China’s chokehold over the critical minerals.