If Hongkongers had to choose one thing to represent their time of fighting for freedom, it would be singing “Glory to Hong Kong” during the anti-extradition movement.

Since then, the unofficial Hong Kong anthem has been characterized as an anti-government song. On multiple occasions, performers who played the song have been arrested and charged by Hong Kong police.

At first, the charges were “playing an instrument without a license” and “misconduct in a public place” but have morphed to “suspected of committing inciting acts.” The change reflects that the public can be found guilty, of not just what they say but also what they sing.

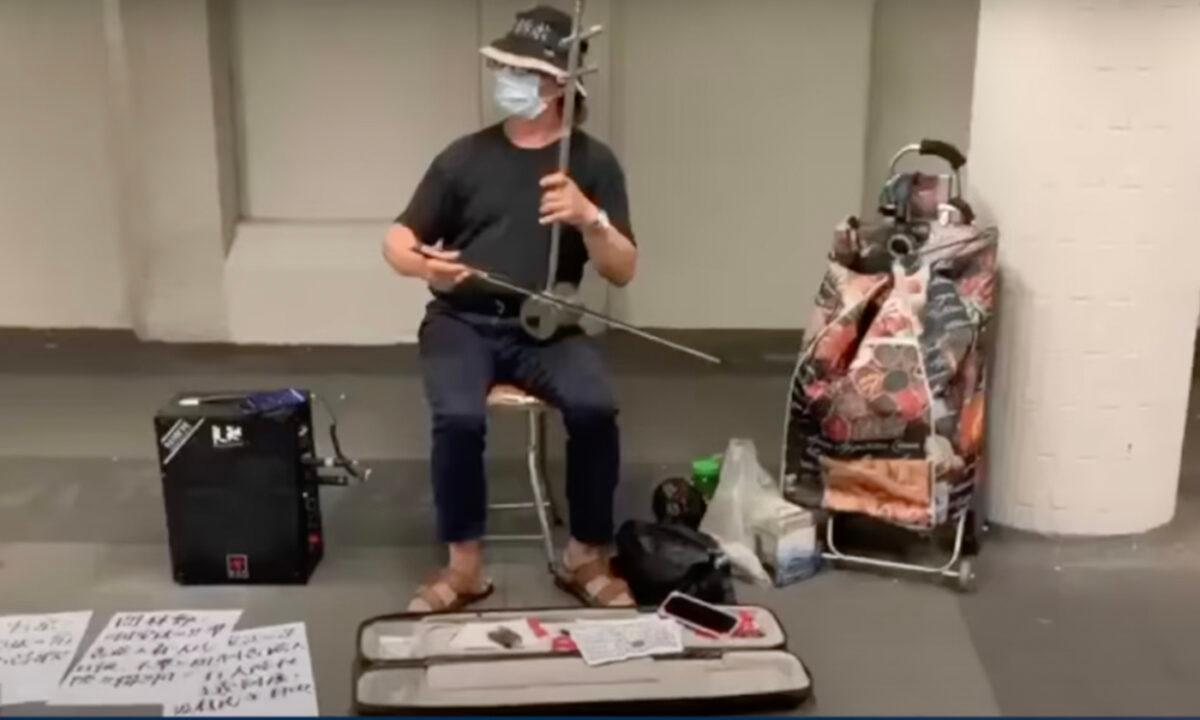

The most recent charges were on Aug. 3, Aug. 18, and Sept. 9, 2021. Li played Glory to Hong Kong on his erhu (a Chinese two-stringed musical instrument played with a bow) outside the Mongkok MTR station. Without permits issued by the Commissioner of Police or legal rights or explanations, the Hong Kong Police issued Li three summonses.

If found guilty, Li could be penalized a maximum of 2,000 HKD (about $255) or three months imprisonment.

Since 2019, Li has been playing “Glory to Hong Kong” in public and has been interrupted by the police a number of times. In May 2020, when he was playing his erhu on a street corner in Yuen Long, some passersby accused Li of making noise and called the police.

When police arrived, they gave Li a ticket and charged him with playing an instrument without a permit. Li went to Tuen Mun Magistrate’s Court on Sept. 1, 2020.

Li was adamant about not pleading guilty. He thought the police ticketed and charged him only because they wanted to suppress his playing of “Glory to Hong Kong.”

Li said, “It is my right to play erhu. I will defend myself with the International Covenant On Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights.”

Isn’t Hong Kong Under ‘One Country, Two Systems?’

The 68-year-old was again given a ticket and summoned to court for “playing an instrument without a permit.”This time he was accused of playing “Glory to Hong Kong” at Tung Chung Bus Terminal on April 29, 2022.

When the court inquired about the case in July, Li denied the charges. He also pointed out, “I used to play in the UK, Thailand, even on the streets of mainland China. Why can’t I play on the streets of Hong Kong? Isn’t Hong Kong supposed to be ‘one country, two systems?’ So why can’t I play freely in Hong Kong?”

At the time, the provisional magistrate Tsang Hing-tung responded, “No, you can’t.”

The erhu player says he had gone to the police station twice to apply for a permit to perform, but the officers refused to issue it, citing “the pandemic” as the reason.

The case resumed in August. When the police officers testified, they said they arrived at the scene after receiving a noise complaint. They found Li playing his music amplified with a loudspeaker, and it was audible 20 meters (65.6 ft.) from where Li was seated.

The police officers then said they asked Li to show his identity card. Li planned to pack up and leave and stated that if the police wanted to summon him, he would continue playing his erhu.

As Li did not have a legal representative, he defended himself in Mandarin. Li asked the specific officers about the nature of “Glory to Hong Kong.” Provisional Magistrate Tam Lap-fung said it was irrelevant to the case. “The key is whether the defendant was playing an instrument with a permit.”

Ultimately, the court decided that the prosecutors did not provide all indicted elements to prove the charges.

The magistrate thought that the evidence only proved that the defendant was playing the erhu at the time in question, but not whether he had a permit. Hence Tam ruled insufficient evidence and revoked the charges. Li was also granted 500 Hong Kong Dollars (about $ 64) for his litigation fees.

Li expressed his satisfaction with the ruling outside the court and said he would perform on the street again. Li thought that summons issuance was a waste of time. He emphasized, “The truth will also be on our side. Glory will always belong to Hong Kong.”

However, the closed case took a strange turn. Provisional Magistrate Tam Lap-fung overturned his verdict four days later.

The case was heard on Sept. 2. Tam claimed that upon reviewing the regulations, he found the charges involved in Li’s case did not require the prosecution to submit evidence. The court asked Li to defend against the established evidence and revoked his litigation fee.

Li said that playing his erhu was nothing political. “I was only performing notes on a music sheet.”

A Street Performer With Multiple Summonses

Li was dealing with multiple summons tickets for playing music on the street. In another case, he was summoned three times by the Hong Kong Police on Aug. 3, Aug. 18, and Sept. 9, for playing an instrument in public without a permit. He was playing “Glory to Hong Kong” in all cases.The court delayed his case, so the prosecutors said they would wait to hear the verdict Li would receive on Oct. 3 for the same charge.

The case adjourned once again, pending clarification of legal issues.

Li opposed the prosecution’s delay, saying the case had been dragging on for too long. It not only exhausted him, but also wasted a lot of government resources.

Police Arrest and Suppress Street Performers

Li’s prosecution isn’t the first time police targeted street performers, particularly those who sang about social issues.In July and August 2020, Olive Ma, a Filipino-Chinese street performer, was arrested twice after the National Security Law was implemented for singing the English version of Glory to Hong Kong. The police confiscated Ma’s instruments and stopped him from playing. Initially, the police charged Ma with obstructing a police officer’s work and possessing offensive weapons.

However, the police amended the charges to noise disturbance caused by a musical instrument and noise disturbance caused by a loudspeaker.

Music Related to Social Movement is a Crime

Although the song “Glory to Hong Kong” was never characterized by Hong Kong law as violating national security or dividing the country, the government officials have already classified it as seditious and “closely related to illegal events.”On the evening of Sept. 19, 2022, the day of Queen Elizabeth II’s state funeral, Hong Kong residents flocked to the British Consulate General to pay tribute to the late Queen.