A group of farmers from Shanghai and a couple from Hubei Province have filed lawsuits against the Chinese central government, seeking compensation for alleged government malfeasance. In a rare sign of direct protest against the Communist Party leadership, premier Li Keqiang was listed as one of the defendants.

The plaintiffs have repeatedly appealed their grievances to government agencies via formal petitions, to no avail.

They have filed lawsuits as a last resort.

“Our painful experience tells us that petitioning is an impassable path, and that [the process] is not protected or supervised by the law,”the Shanghai farmers wrote in their lawsuit.

The lawsuits were mailed to courts in Beijing. At the time of writing, the plaintiffs have not yet received a response from the courts.

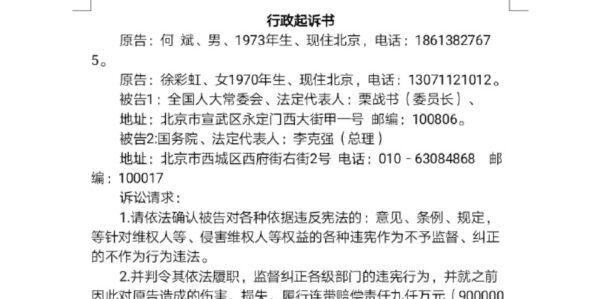

Hubei Couple

47-year-old He Bin and his 50-year-old wife Xu Caihong filed their lawsuit with the country’s highest court, the Supreme People’s Court, on Oct. 24. They named as defendants the head of the central government, Li Keqiang, and the head of China’s rubber stamp legislature, Li Zhanshu.In the lawsuit, He and Xu claimed that officials forced their restaurants to shut down. They traveled to Beijing to petition their grievances. However, they were frequently harassed by police.

In several phone interviews with the Chinese-language Epoch Times, the couple spoke of their experience appealing to the authorities.

He and Xu were workers at the Hubei Chemical Fiber Factory in Xiangfan city until around 2000, when their employer laid off staff.

The couple also owned a store in downtown Xiangfan to sell goods to young consumers, such as fine stationery, fashionable gifts and jewelry, and so on. After getting laid off, they devoted all their time to running the store. The business was flourishing, which angered their competitor—who had ties with local officials and gangsters, they alleged.

In 2001, He was detained by local authorities, on what he said were false charges. Xu appealed to government agencies for half a year, hoping to set him free. Months later, he was finally released with all charges dropped.

However, soon after He was released, gangsters broke into their store and destroyed almost all the goods. The thugs told the couple that they were operating under orders from an official at the Fancheng District Court, He said.

The couple were forced to shut down their store and began a six-year long legal fight, including filing lawsuits against owners of the competitor store and officials at the district court. They also traveled to the petition bureau in Wuhan (the province’s capital) and the national petition bureau in Beijing.

One winter, Xu, while pregnant, was detained by police at a so-called “law education center” in Fancheng district due to her petitioning. Several plainclothes officers surrounded her and beat her until she suffered a miscarriage. Her injuries caused her to become unable to conceive again.

In 2008, the couple accepted the compensation district authorities arranged for them, which was 120,000 yuan ($18,150) in cash with social security insurance for both of them. He and Xu then used the money to operate a small restaurant, located inside a building owned by the Fancheng District Court.

In 2010, the court suddenly announced that the building needed to be renovated, and drove away all tenants, including the couple—though their leases were not up yet. After He and Xu moved out of the building, the court rented out the restaurant at a higher price to another tenant, without doing any renovations.

He and Xu then started their second round of petitioning in Beijing.

Being listed on authorities’ blacklist, He and Xu were stopped by police on the streets in Beijing after surveillance cameras detected their location. A small restaurant they operated in Beijing was then raided by police during the winter of 2017. The police told the landlord to throw away all their belongings, the couple said.

In the past few years, they were detained multiple times while petitioning during the Chinese regime’s national conferences and key meetings in Beijing.

He and Xu wrote in the lawsuit: “We think that the inactions of defendants [Li Keqiang and Li Zhanshu] caused, aggravated, and encouraged all these infringements [on our rights]...We ask defendants to actively correct themselves and take responsibility.”

Shanghai Farmers

Shi Kehua and 55 fellow farmers lived in Gaodong, Gaonan, and Yangyuan townships in Chuansha county, Shanghai.In 1992, Shanghai divided these three townships into the Pudong Waigaoqiao Free Trade Zone. The 56 farmers and their neighbors had to give up their homes to the local government to redevelop. They signed contracts in which the government promised to arrange new equivalent accommodations for them.

However, the apartments assigned to the farmers were much smaller than their original homes.

The farmers have repeatedly petitioned and complained to the Shanghai municipal government for decades, but received no response.

On Aug. 20, 2018, the farmers applied to the Shanghai government for property protection, according to official records. The government did not respond to their request.

A few months later on Dec. 20, the farmers filed an application for authorities to reconsider their request for property protection—a right granted by China’s Administrative Reconsideration Law. Six days later, the Shanghai government replied, saying the farmers must go through the petitioning process to make the request.

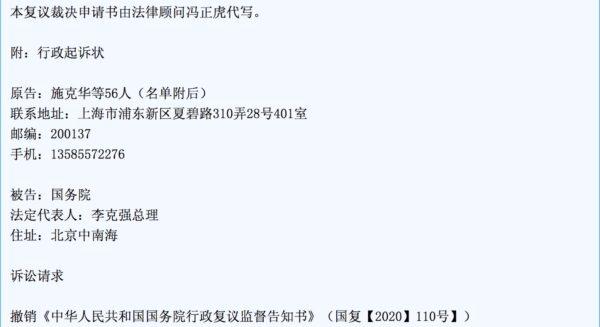

The farmers felt frustrated and filed a new reconsideration application to China’s cabinet-like State Council on Jan. 5, 2019.

Having waited for over a year, the farmers finally got a response on April 3 this year, in which the State Council claimed that they did not have enough documentation to support their application.

“Which documents did we miss?” the farmers asked in the lawsuit. “We have plenty of verification documents.”

On Oct. 6, the farmers filed a lawsuit with the Beijing First Intermediate People’s Court against the State Council, which is headed by premier Li Keqiang, to ask the central government to reconsider their case again and give them redress.

Petitioners in China are frequently harassed and detained.

Every year during the rubber-stamp legislature’s sessions, thousands of petitioners would gather in front of the national petition bureau every day. But police frequently arrest them or drive them back to their hometowns.

It’s unclear how many petitioners are in China now. Hundreds of them have immigrated overseas and sometimes show up to protest Chinese leaders’ state visits.