A male resident of China’s Shaanxi province admitted to setting his house on fire on Lunar New Year’s Eve, burning his wife to death so that they could eventually be buried together in accordance with rural folk beliefs.

According to a Yulin city police report, Zhu Liantang, 69, has been detained for the murder of his wife Li Chun, 35, who was a mentally and physically disabled woman.

Zhu Liantang is still under investigation and has so far refused to reveal his motive.

The rural pagan belief in Shaanxi requires a deceased person to be buried together with a partner’s bones to rest in peace. The wealthy can spend up to $14,800 (100,000 yuan) to purchase a stranger’s remains. Those who cannot afford this price point are typically laid to rest accompanied with paper dolls.

Zhu Liantang’s daughter had considered buying bones for her father’s passing but was unsure about the legality of doing so. Her parents had divorced many years ago, and Zhu Liantang had raised her on his own.

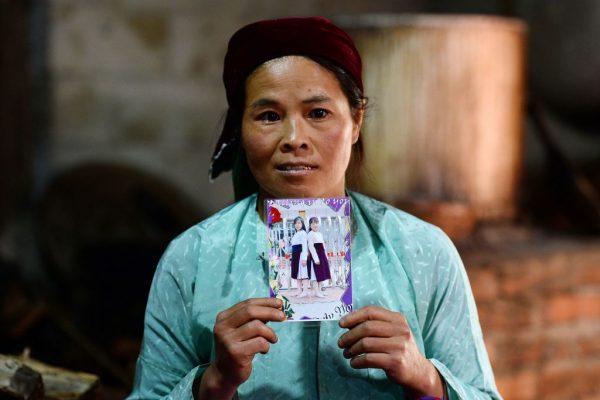

She found Li’s father, who wanted someone to take care of his daughter through marriage. The union was arranged and Li’s family was paid $357 (2,400 yuan) for the bride.

Li had polio, could not speak or walk, and had a severe mental disability. Zhu’s daughter and grandson had expected to take care of Li until her natural passing, and eventually bury the husband and wife together according to the folk belief. Their father had other intentions.

Chinese online commenters weighed in on the case.

Posthumous marriage is a custom which has been observed for more than a thousand years by some living in China’s provinces of Shaanxi, Shanxi, Gansu, Guangdong, and Henan.

A similar case in 2009 saw a man sentenced to death for killing a pregnant woman in Shaanxi province and selling her body to the family of a deceased man for $3,273 (22,000 yuan).

Qi XianSheng, a man who is familiar with Shaanxi’s burial rites, notes that it is common for people living in the rural area to conduct marriage ceremonies for deceased single men.

Qi believes that Li’s father was trying to marry his disabled daughter into a better life because the Chinese government had “no intention” to provide them with any aid.

“Social security can’t keep up, and parents worry that after their deaths, no one is around to look after their child. They wanted to find a home for her but instead, he killed her for his own burial.

“He is afraid that because she is mentally ill, after his death, she might not end up being buried with him. So before he died, he killed her first,” Qi said.

A local government official who was contacted for comment denied that the folk custom existed in the area.