A senior official drove by. Then the anti-riot police turned up. They rained down punches and kicks, and threw dozens of people into vans. One gray-haired woman fainted as the police dragged her away, her back scraping the ground.

City officials told the rest of the dazed protesters in Tianjin, a megacity in eastern China, that they would need to go to Beijing to appeal if they wanted the 45 prisoners released.

So they did—although the Tiananmen Square massacre a decade earlier still scarred them.

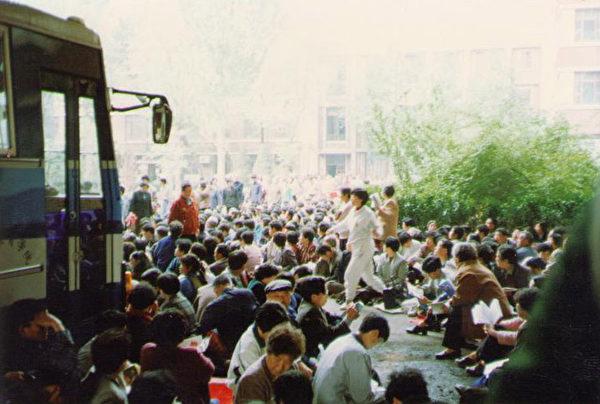

Ultimately, 10,000 people congregated quietly in Beijing on a day in 1999, now remembered as the April 25 appeal—one of the largest protests in communist China’s recent history.

Despite 25 years having gone by, those who were there that day say their issue is as relevant now as it was then.

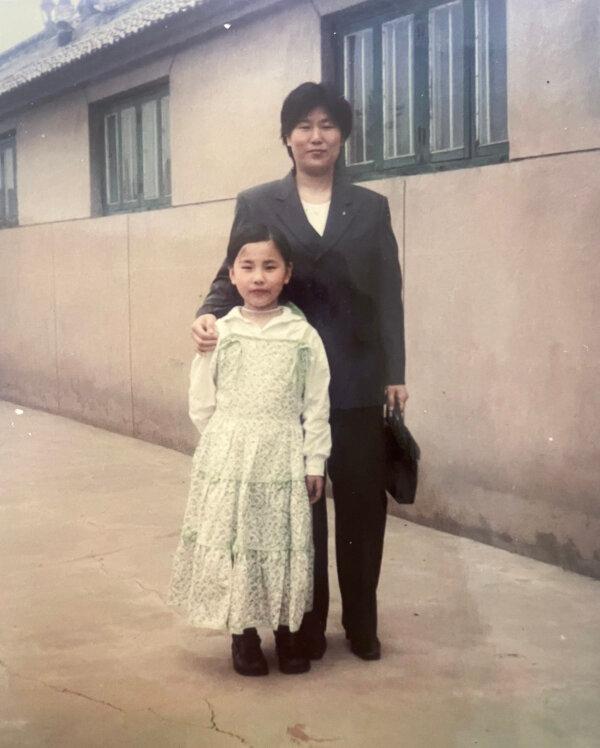

Wang Huijuan, then a 28-year-old local elementary school teacher, had clutched her husband’s arm tightly as she watched the police make arrests in front of her in Tianjin. But it didn’t take long for her to make up her mind to join the appeal for her fellow practitioners’ release. That April 25 morning, she cried as she hugged her 5-year-old daughter goodbye before hopping into a cab to Beijing, 80 miles away.

“I thought at the time that no matter what would happen to me, I had to step forward, to tell my thoughts to the [authorities],” Ms. Wang, now in New York, told The Epoch Times. “If I don’t come back, so be it.”

In 1999, Falun Gong, the meditation she practiced, was popular in China. About 70 million to 100 million Chinese people embraced the idea of living their lives based on the principles of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance, the central tenets of the practice. Ms. Wang credits the practice for restoring her health and filling her life with “sunshine and hope.”

But the environment was changing.

Plainclothes police officers monitored Ms. Wang and others in a public park when they gathered to do the Falun Gong exercises. A state-run magazine published an article slandering the practice. When a group of practitioners asked for a retraction, Tianjin’s public security bureau dispatched riot police to beat them up and make arrests. They arrested 45 practitioners.

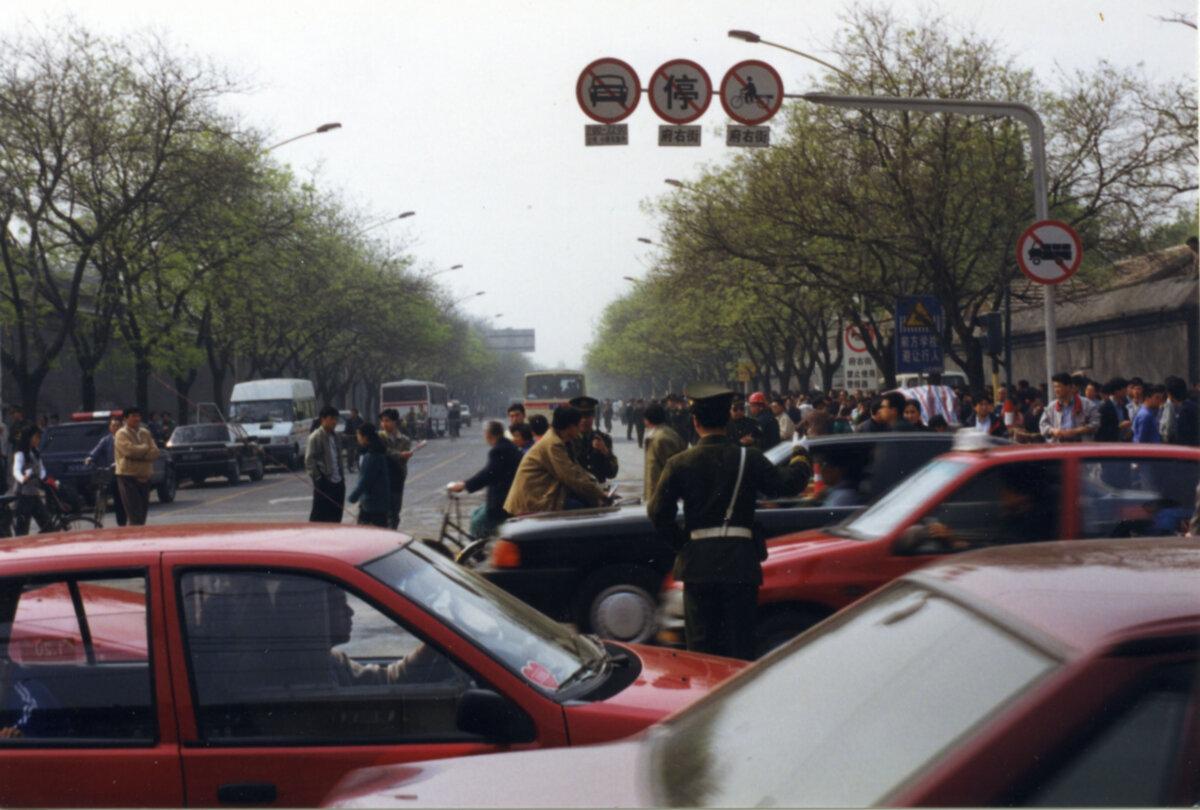

As word of the police brutality began to spread, Falun Gong adherents around the country decided to travel to Zhongnanhai, the compound for the top Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership, to ask for the release of the Tianjin detainees and for the freedom to practice their beliefs.

‘Beijing Welcomes You’

At about daybreak, Ouyang Yan, then a 48-year-old administrative worker at the Communication University of China in Beijing, began biking toward Zhongnanhai. She was among the first to arrive. Few people were on the streets, but police cars were parked all around.“We were thinking, did we come too early?” Ms. Ouyang, who now lives in Seattle, told The Epoch Times. “How come there wasn’t anyone?”

Within about half an hour, though, more Falun Gong practitioners joined. Some arrived in the afternoon because they had flown in. There were people of all ages, including those in their 80s and a mother with a 2-week-old newborn.

“I never saw so many people together, even on TV,” Ms. Wang said.

For an unorganized gathering, the practitioners were surprisingly orderly.

They lined up along the pedestrian paths; some walked around to pick up litter. It was peaceful enough that the police, initially tense, gradually relaxed, sitting on street curbs and chatting with each other, according to Ms. Wang. Ms. Ouyang’s daughter stood studying for an upcoming exam, propping books on her parents’ backs.

At one point, Ms. Ouyang heard that some CCP officials inside Zhongnanhai were asking to meet with representatives of the protest. She said she nearly volunteered herself, even though she wasn’t a great speaker.

“That day, I was so confident in myself that I would be able to explain to anyone how great the Falun Gong practice is,” she said.

In the late afternoon, bikers in sleeveless shirts waved to them.

“Beijing welcomes you, hope you come again,” Ms. Wang recalled them saying.

Ms. Ouyang said most of the adherents left the protest by 9 p.m. But she and her husband stayed for another hour. They waited for her mother and joined her in picking up trash around the area.

Zhao Ruoxi, now a Chinese-language teacher in New York, was a host of a state-run radio station in Tianjin in 1999. That evening, when she learned about the detainees’ release, she went to the local police station to pick them up. The local police officials treated them all to an elaborate meal.

Ms. Zhao said the officials told her the arrests were all a “misunderstanding.”

“We didn’t know the situation; if we had, we wouldn’t have arrested you guys,” she recalled them saying.

‘Intention to Frame’

It could have ended there. But just three months later, then-CCP leader Jiang Zemin ordered a nationwide campaign to eradicate Falun Gong.The day Jiang’s order came out, on July 20, 1999, police knocked on the doors of Ms. Wang’s and Ms. Zhao’s homes.

Ms. Wang’s husband, then a state TV anchor, and Ms. Zhao were taken away for interrogation. Ms. Wang’s school detained her the next day.

China’s state-run media distorted facts about the peaceful protest and repeatedly published propaganda about the event, often describing it as a “siege” against the CCP leadership. But some practitioners, now looking back, believe that the Chinese regime had planned it all along.

“When there’s an intention to frame someone, there’s no lack of excuses,” Ms. Wang told The Epoch Times.

She later heard that several Beijing hospitals near Zhongnanhai had been emptied that day, in preparation for treating traumatic injuries.

Ms. Wang said that initially, there was a “sense of terror” in the air.

“Police cars were driving by, one after another,” she said. “It’s the serenity [of the petitioners] that dissolved violence.”

Ms. Ouyang said that when she first arrived and was walking around, she was stopped by police from crossing a bridge that led to Beihai Park, located several blocks from Zhongnanhai. She said that the police officers’ directive indicates that Chinese authorities had made certain arrangements, even before the start of the peaceful protest.

A few blocks south from where they gathered, a large number of police vans were waiting.

‘Best Gift’

Three years later, in 2002, Ms. Wang and her husband were both fired from their jobs and arrested for making DVDs exposing the CCP’s persecution and disproving the regime’s propaganda about Falun Gong. They were imprisoned in separate places for seven years because they refused to sign papers saying they had “transformed,” a euphemism for giving up and defaming one’s beliefs.Their daughter was allowed to visit them twice a year.

“When she saw me at 8 years old, I asked her, ‘Do you hate mom?’ She said she didn’t. I asked her, ‘Do you want mom to “transform” and get home to take care of you, or do you want me to keep up?’ She told me, ‘Mom, keep up.’”

Ms. Wang hugged her and cried.

“Except for in mainland China ... you can practice Falun Gong freely, [everywhere, and] promote it in public,” Ms. Zhao said.

“Only the CCP arrests people who practice truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance.”

The April 25 appeal has always inspired Ms. Wang.

“It was an honor to be standing there,” she said.

“Sometimes, you might think you are all alone, but when you think about these people on April 25, so many of them all standing there, you realize that you are not actually alone. In every corner of the country, there’s someone like you, suffering pain and sacrificing themselves in silence. They are sacrificing their all for the truth.”

It was an experience to overcome fear and speak the truth, she said.

“It was a sacred feeling.”

After her release, Ms. Wang ran a bridal store. One day, a young man of about 30 came in and chatted to her about how he had listened to an overseas television channel reporting how peaceful the April 25 appeal was. He wanted to know more about Falun Gong.

“Who dared to go to Tiananmen to petition after June 4?” he said, referring to the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre. Ms. Wang gave him “Zhuan Falun,” the meditation practice’s main book of teachings. A few months later, the man invited Ms. Wang and her husband to dine in his home.

During the meal, Ms. Wang said, he raised his glass and said: “Thank you for letting us know about truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance. This is the best gift to us.”

‘A Beacon of Hope’

The day of the appeal, Elizabeth Huang, who was 1,000 miles south, in the city of Guangzhou, received a phone call from a fellow practitioner at about 6 p.m. local time. The practitioner told her about the protest in Beijing, and Ms. Huang immediately felt the urge to join. She considered booking an early flight the next day to Beijing.Her trip never materialized. At about 10:30 p.m., Ms. Huang contacted a practitioner who had been at the protest and learned that the gathering had just ended. Initially, she said she was “very shocked” to learn that Chinese authorities had agreed to release the detained practitioners, thinking that people in China usually had to go through all kinds of trouble to get someone released.

“That night, I had a very good sleep,” Ms. Huang told The Epoch Times. “I believed at the time that the dust had settled, and I wouldn’t have to worry” about practitioners being mistreated by authorities in the future.

Ms. Huang, now 53, lives in the San Francisco Bay Area and has been in the United States since 2013. She left China in 2009 because of the persecution.

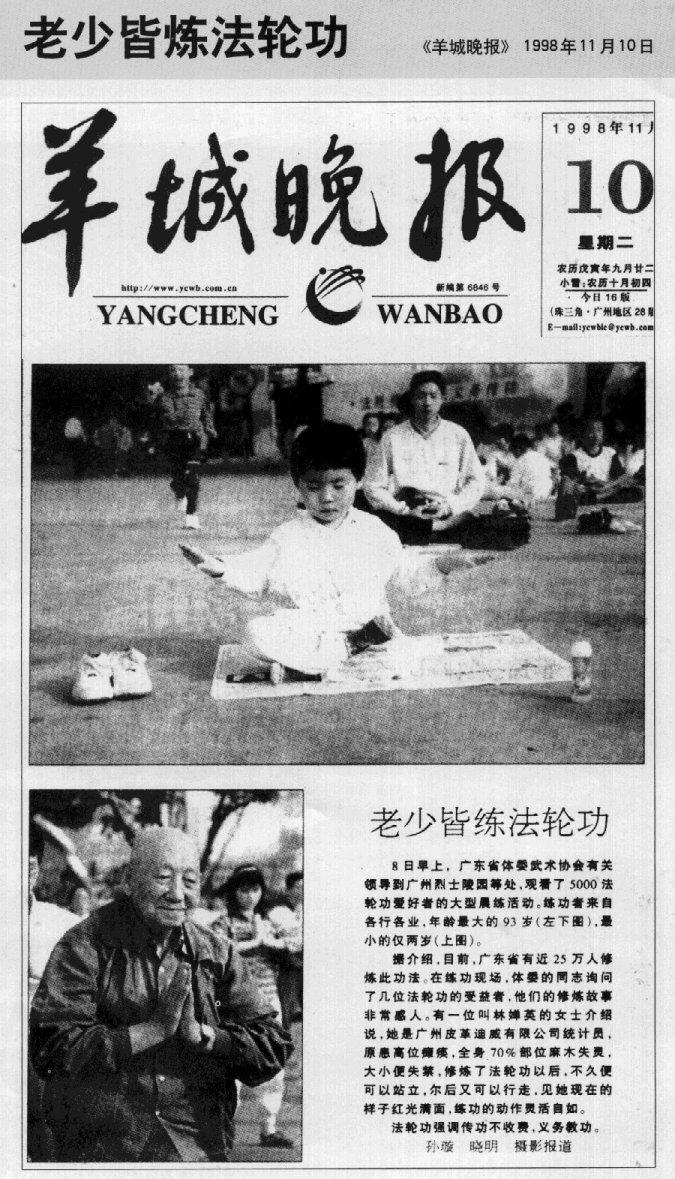

Before leaving China, she worked for a state-run media outlet and once assisted in covering a local event about Falun Gong before the start of the CCP’s persecution.

She started working at the Guangzhou-based newspaper Yangcheng Evening News on Dec. 21, 1994. In December of that year, while still an intern, she used her press pass to attend a lecture by Falun Gong’s founder, Mr. Li Hongzhi, at a local sports auditorium. She began practicing Falun Gong three years later.

But in the months after the article’s publication, she said, her workplace slowly changed. She recalled that her co-workers and superiors, likely having been exposed to other state-run media’s negative reporting about Falun Gong, began reminding her that it might not be a good idea to take up the practice.

Ms. Huang said her colleagues involved in publishing the 1998 article were subjected to a “self-criticism” process and forced to say it was a mistake to cover the Falun Gong group exercise.

Ms. Huang still regrets not being able to join the appeal on April 25, 1999.

She wishes she had been there as “one of the lights” making up a “beacon of hope and goodness.”