Breaking

Trump Extends TikTok Deadline for Another 75 Days

China retaliated on Friday to Trump’s sweeping 54 percent tariffs with its own 34 percent tariffs on all U.S. goods.

The Biggest Financial Scandal in History—And You May Be Part of It: Roger Robinson

Tens of millions of Americans are unwittingly investing in Chinese companies involved in military weapon production, surveillance, and human rights abuses.

‘Audrey’s Children’: This Doctor Should be Nominated for Sainthood

While not a stellar biopic, “Audrey’s Children” is sure to inspire good deeds in medical profession aspirants and is definitely worth a watch for everyone.

Standing at the Edge of Eternity: How to Visit the Grand Canyon

From lightning storms to the whisper of the Colorado River, the Grand Canyon offers awe at every turn.

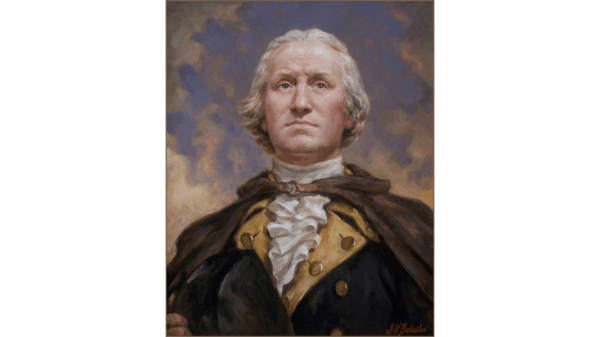

When George Washington Calmed a Mutiny

In this first article of the series “When Character Counted,” we visit a moment when a pair of spectacles helped save the American experiment of democracy.

Most Read

Top Stories

Dow Jones Slides More Than 1,400 Points Amid Tariff Announcements

During Friday morning trading, the three major U.S. stock indexes saw another day of declines.

How Cory Booker Broke the Senate Filibuster Record

The arduous 25 hour, 5 minute speech required days of physical preparation for the 55-year-old senator.

IRS Sends Last-Minute Tax Reminder to Millions of Americans in Disaster Areas

The agency also sent a reminder to taxpayers living and working abroad.

Here’s How Much the US Is Tariffing Each Country

Aside from a universal 10 percent levy, roughly 60 countries will be hit with additional reciprocal tariffs.

South Korea’s Constitutional Court Upholds Impeachment, Removes President Yoon From Office

The court votes 8-0 that the president violated the Constitution.

▶The Biggest Financial Scandal in History—And You May Be Part of It: Roger Robinson

Tens of millions of Americans are unwittingly investing in Chinese companies involved in military weapon production, surveillance, and human rights abuses.

RFK Jr. Says Some Layoffs Were Mistakes, Workers Being Reinstated

The CDC’s lead poisoning prevention team are among the personnel who were wrongly terminated.

Trump Admin Will Ask Congress to Codify Spending Cuts, OMB Official Says

Eric Ueland, acting OMB chief of staff, testifies at his nomination hearing before the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs.

Trump Says China Panicked By Imposing Retaliatory Tariffs

‘My policies will never change,’ Trump said on social media.

Federal Judge Temporarily Blocks HHS From Cuttting $11 Billion in Public Health Funding

A coalition of states is likely to succeed in their arguments that the funding block is unlawful, Judge Mary McElroy said.

Trump Administration Plans to Freeze $510 Million in Brown University Grants

Brown has become the fifth Ivy League school to have federal funding targeted over anti-Semitism concerns.

▶Shen Yun Shows ‘Divine Expression of Something That We All Need to Connect With’: Company Co-founder

At the Thousand Oaks Civic Arts Plaza in Thousand Oaks, California, Shen Yun Performing Arts mesmerized theatergoers on March 26.

Payment Options: IRS Issues Reminder to Taxpayers Unable to Clear Balances in Full

Taxpayers may qualify for settling their dues for a lower amount in some cases, the agency said.

Israel Expands ‘Security Zone’ in Northern Gaza

The Jewish state issued evacuation warnings in the area on Thursday, which saw hundreds of residents leave.

US Economy Adds Hotter-Than-Expected 228,000 New Jobs in March

The unemployment rate ticked up to 4.2 percent from 4.1 percent.

China Retaliates With 34 Percent Tariffs on US Goods

The tariffs will come into effect from April 10.

Tracking Trump’s High Level Appointments, Senate Confirmations

The Senate is undertaking the confirmation process for the president’s new administration.

Supreme Court Weighs Wave of Challenges to Trump Agenda

The president has asked the high court to review multiple of the 100-plus lawsuits against his administration.

Republicans May Override Senate’s Nonpartisan Referee to Pass Trump’s Agenda: What to Know

The Senate parliamentarian plays a key role in budget reconciliation, which congressional Republicans are using to advance the president’s policy goals.

In-Depth

Hong Kong’s ‘Superman’ in Beijing’s Crosshairs Over Sale of Panama Port Assets

Billionaire tycoon Li Ka-shing is engaged in a protracted power struggle over ports in the Panama Canal.

Grow Your Own Bouquets: How to Start a Cut Flower Garden

Don’t worry about plant size, balance, complementary colors, and the overall design—simply plant what you like. These smart techniques will help.

Special Coverage

Special Coverage