Commentary

When it comes to evil, profit-greedy polluters, the left and its allies in the establishment media have you conditioned to think reflexively of Big Oil. But as your ears burn from hearing the screams about the burning of fossil fuels sacrificing humanity on the altar of corporate avarice, you might be surprised to discover a less-than-well-known fact: “the Cloud” of thousands of countless, massive, very much down-to-earth servers providing physical storage of data for the more than five billion people on the planet who use the Internet imposes a massive carbon footprint.

Considering the extent of wokeness and leftist radicalism within Silicon Valley, where workers apparently practice activism as much as they perform work—to the extend that a former high-ranking Facebook employee has compared its workplace to a “cult”—the hypocrisy is shameless.

According to Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), “We will have to mobilize our entire economy around saving ourselves and taking care of this planet.” Fellow Squad member Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.) on the House floor last month accused the “greedy oil and gas companies” of “price gouging our residents at the pump and poisoning the air they breathe and the water they drink.” (In fact, even investigative journalists on the left know that oil industry price gouging is a myth.)

Last summer, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) blasted the oil, pharmaceutical, insurance, and even food production industries, charging that using the COVID pandemic and the war in Ukraine as excuses, all “the corporate world has done is use all of that to substantially raise prices in America,” and there should be a “windfall profits tax on those crooks.”

Oddly, Big Tech is never high on the left’s list of corporate monsters, if they are there at all. It’s no mystery why: ranging from trailblazing the radicalization of society to financing Democrats’ campaigns, the computer industry has for decades been squarely and dependably on the left’s side.

There is no denying, however, that the corporations that power the Internet, and who have turned cyberspace into a titanic mega-hard drive encompassing in excess of 1 billion gigabytes, have committed transgressions against the “green” god rivaling those of which the oil and gas industry is accused.

According to University of Maryland professor of digital studies Jeffrey Moro, who is working on a book on the Cloud based on his dissertation, “The Internet cannot function without enormous expenditures of energy for cooling and humidity control."

This confluence of air-conditioning and the Internet, which I term “atmospheric media,” illuminates how inhuman, and inhumane, the Internet’s life cycles have become in our climatological moment.

Last year, MIT anthropologist Steven Gonzalez Monserrate studied what he calls the “ever-expanding, carbon-hungry Cloud,” drawing firsthand on “five years of qualitative research and ethnographic fieldwork in North American data centers,” the facilities where the giant servers we all depend on are located. He found that “the Cloud now has a greater carbon footprint than the airline industry. A single data center can consume the equivalent electricity of 50,000 homes. At 200 terawatt hours (TWh) annually, data centers collectively devour more energy than some nation-states. Today, the electricity utilized by data centers accounts for 0.3 percent of overall carbon emissions, and if we extend our accounting to include networked devices like laptops, smartphones, and tablets, the total shifts to 2 percent of global carbon emissions.”

The left asks rhetorically why the fossil fuel and pharma industries need so much of what they characterize as excess profits. It’s because it takes a fortune to innovate, to have scientists travel long ways down what turn out to be empty roads in order, eventually, to discover the means of drilling sideways to access once impossible-to-reach deposits of oil and gas, or to discover cures and treatments for particular strains of leukemia or for Lou Gehrig’s disease. The left might similarly ask why the Cloud needs data centers “designed to be hyper-redundant: if one system fails, another is ready to take its place at a moment’s notice, to prevent a disruption in user experiences,” quoting Monserrate.

Examples of this are the data centers’ air conditioning systems “idling in a low-power state, ready to rev up when things get too hot.” As he quips, “The data center is a Russian doll of redundancies: redundant power systems like diesel generators, redundant servers ready to take over computational processes should others become unexpectedly unavailable, and so forth.” He points out that in some cases, only 6 to 12 percent of the energy consumed is for active computational processes.

The Cloud also thirsts. Many data centers need chilled water flowing through their racks of server. The National Security Agency’s Utah Data Facility consumes seven million gallons of water every day, with the residents of Bluffdale, Utah, paying the price with water shortages and blackouts. In reaction, Google and other tech companies have promised better “water stewardship” in the future.

Data centers can expel 150,000 pounds of carbon dioxide into the air every year, powered as they are by diesel instead of cleaner forms of energy because of diesel’s reliability. Some 70 percent of global Internet traffic passes through the Ashburn, Virginia, area’s “data center alley,” and backup servers means as much as 90 percent of the energy it takes from the electrical grid can be wasted.

And yet with data traffic expected to increase by 150 percent over the next several years and data-storage infrastructure possibly tripling over the next decade, the trend is toward “hyperscale” data centers, with Amazon, Google, and Microsoft owning half of these often football field-sized locales encompassing tens of thousands of racked servers. The cooling of existing server farms alone consumes more energy than the countries of Argentina, Egypt, and South Africa combined.

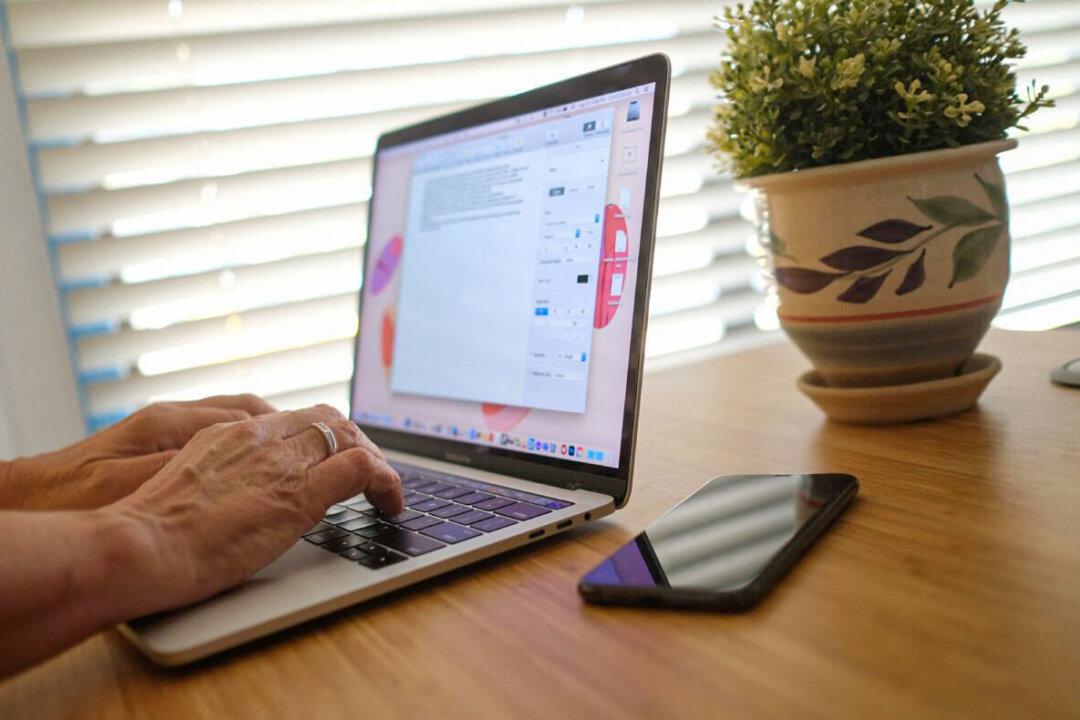

So, the next time a politician on the left during a hearing accuses Big Oil of polluting the planet, someone should point to the carbon-guzzling laptop or tablet from which he or she is reading the staff-prepared questions, or the smartphone in that politician’s pocket. We have all come to depend on computers—nearly as much as we do on gasoline and heating oil.