The arguments about this often-forgotten U.S. Treasury Secretary continue a century later.

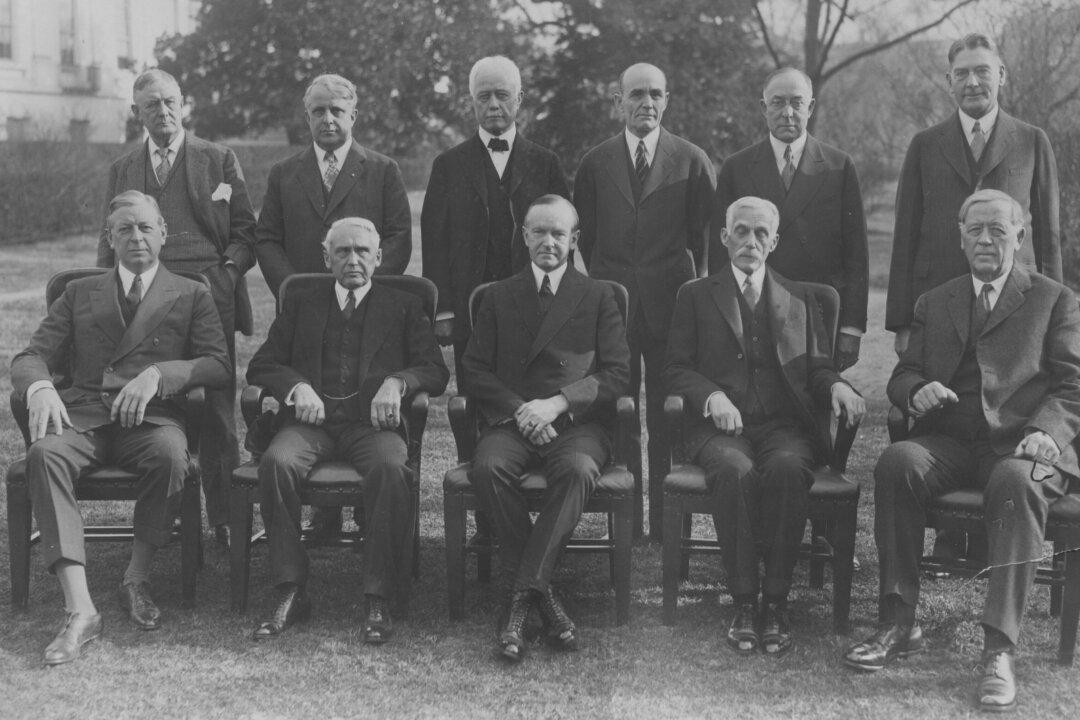

The policies and writings of 1920s U.S. Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon touch on much of what Americans debate today: Taxes, economic growth, and inflation.

The arguments about this often-forgotten U.S. Treasury Secretary continue a century later.

The policies and writings of 1920s U.S. Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon touch on much of what Americans debate today: Taxes, economic growth, and inflation.