Commentary

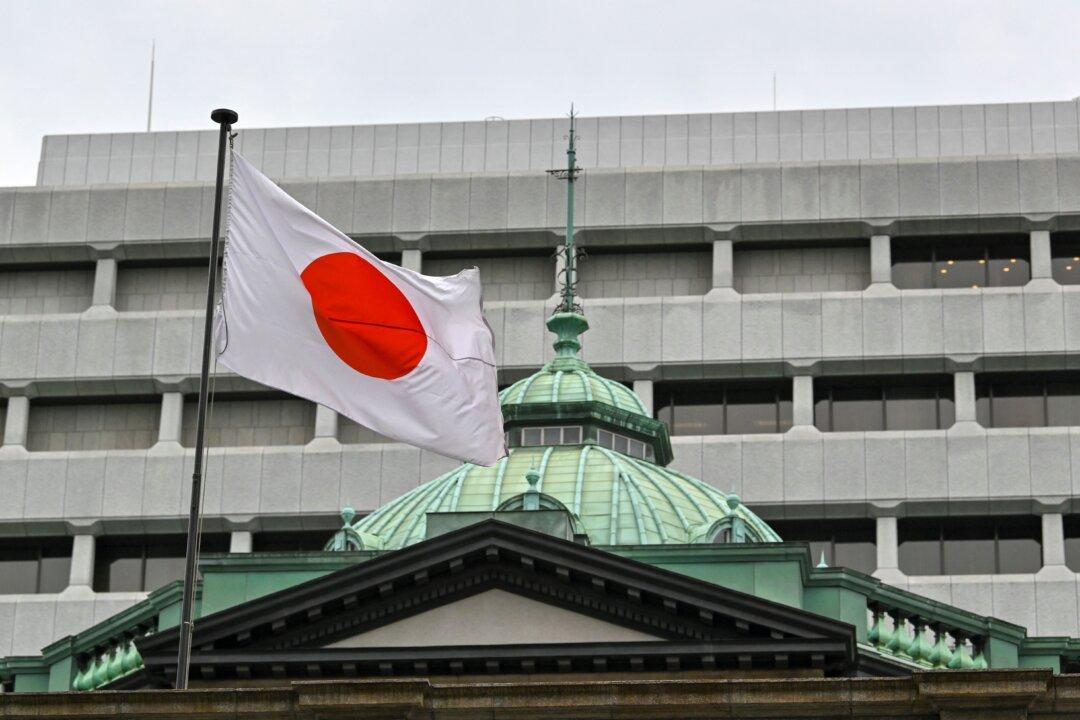

On March 19, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) raised its interest rate paid to commercial banks’ deposits with the central bank for the first time since 2007.

On March 19, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) raised its interest rate paid to commercial banks’ deposits with the central bank for the first time since 2007.