News Analysis

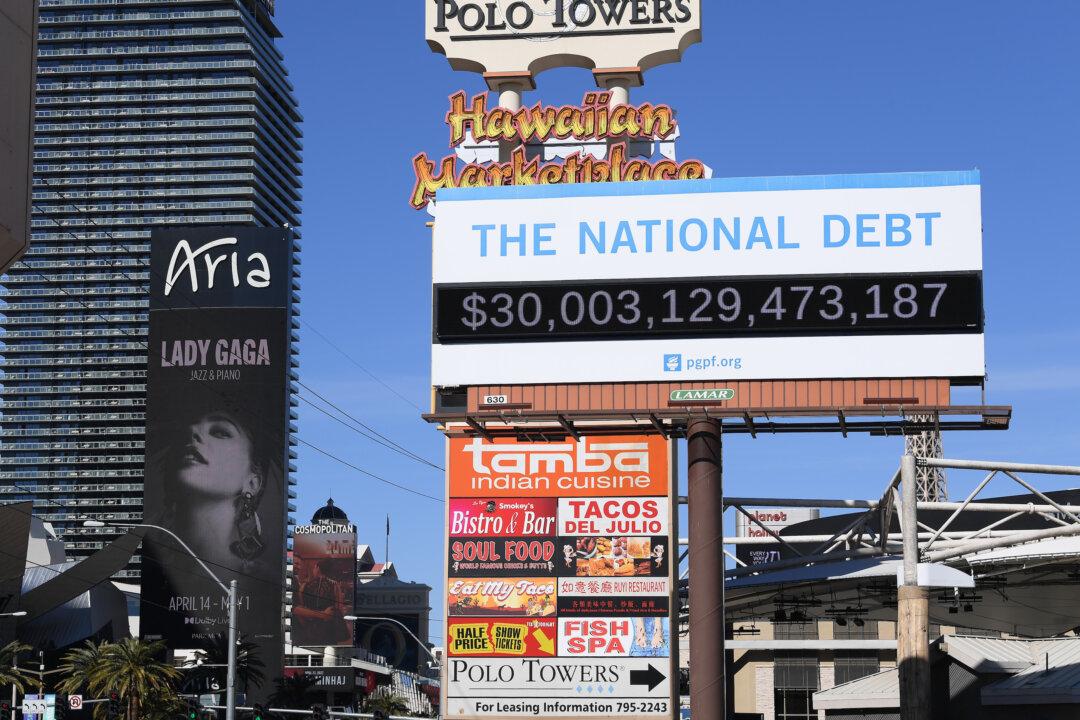

In 1970, inflation wasn’t excessive, but it was becoming a problem. It worried many Americans, including those facing reelection in 1972. The annual inflation rate in the United States was only 5.7 percent, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the prime interest rate had climbed to 8 percent, the Federal Reserve Board reported.