The question of where China has obtained organs for the tens of thousands of transplants that have been conducted there over the last decade is a vexing, contentious and crucial one. Everyone knows the overwhelming source is “executed prisoners”—but in China, who does that include?

State Organs: Transplant Abuse in China, published in July with contributions from a dozen specialists in the field aims to answer that question and elucidate the broader issue of organ sourcing practices in China. The Epoch Times spoke to Dr. Torsten Trey, the co-editor of the book, with Canadian human rights lawyer David Matas, about the aims of the book and what fresh information and insight it provides to the discussion. Dr. Trey is also the Executive Director of the medical group Doctors Against Forced Organ Harvesting, which holds public forums about the topic.

One of the first strange things to note about the Chinese organ transplantation system, according to Trey, is the way that organs can be obtained on short notice. In the course of his medical advocacy work, Trey found that many doctors in the West did not even know about this irregularity.

“If you just tell them that the Chinese can provide organs within two weeks, and that they can schedule a transplantation for a specific time, then after five to ten minutes most doctors immediately understand that there’s something wrong. That cannot be. How can that be?”

China has no effective organ donation program, and the official explanation, that criminal prisoners sentenced to death are the source of organs, has numerous problems. Criminal prisoners are a source of dubious reliability because around half of them have hepatitis B, a viral infection of the liver that disqualifies one from donating organs, according to a study cited by David Matas in State Organs. They are also executed soon after being sentenced to death, according to research by former UN Rapporteur on Torture, Manfred Nowak.

Organ donors need to be kept on hand for when they are needed by a recipient, which would preclude many death row executions. If executed criminal prisoners were actually the source of organs, it would mean that the Chinese regime would have to be executing at least 100,000 people a year to guarantee the ability to perform 10,000 transplants, according to Matas’s analysis. This figure is over 50 times the number of executions carried out in 2008, as estimated by Amnesty International. (Their estimates were discontinued after 2008.)

“Killing for organs became part of transplant medicine,” Trey writes.

Several of the essays in the book examine this question and conclude, as previous studies have, that a primary source of organs has been prisoners of conscience, specifically practitioners of Falun Gong, who disappeared by the hundreds of thousands into the communist regime’s system of prisons and labor camps. Those institutions then work closely with military hospitals to turn the bodies into profits. While they languish in prison camps, they are blood tested and put onto a registry, and when they are matched with a recipient they are taken away and killed for their organs, according to the available research.

David Matas gives a best guess — since no actual data is available — that every year, to supply 10,000 transplants, 1,000 death row prisoners are killed for their organs, 500 transplants come from living donor relatives, 500 come from Uyghurs, Tibetans, and Eastern Lightning House Christians, and 8,000 come from Falun Gong practitioners.

The abuse of medicine apparent in such a scheme helped Trey and Matas rally a group of like-minded experts to put together the present volume. There are two essays analyzing the numbers question; an essay by Arthur L. Caplan, head of the Division of Bioethics at the New York University Langone Medical Center, pointing out the problems with “polluted” organ sources; an exploration of one doctor’s personal realization of the need to do something about China’s abusive organ sourcing practices, contributed by Jacob Lavee, director of the Heart Transplantation Unit at Sheba Medical Center, one of the most prestigious in Israel; a short and sharp nudge to the academic community in light of all the preceding by Gabriel Danovitch, Medical Director of the Kidney and Pancreas Transplant Program at UCLA’s School of Medicine; and sundry other contributions taking one or another illuminating tack to the issue.

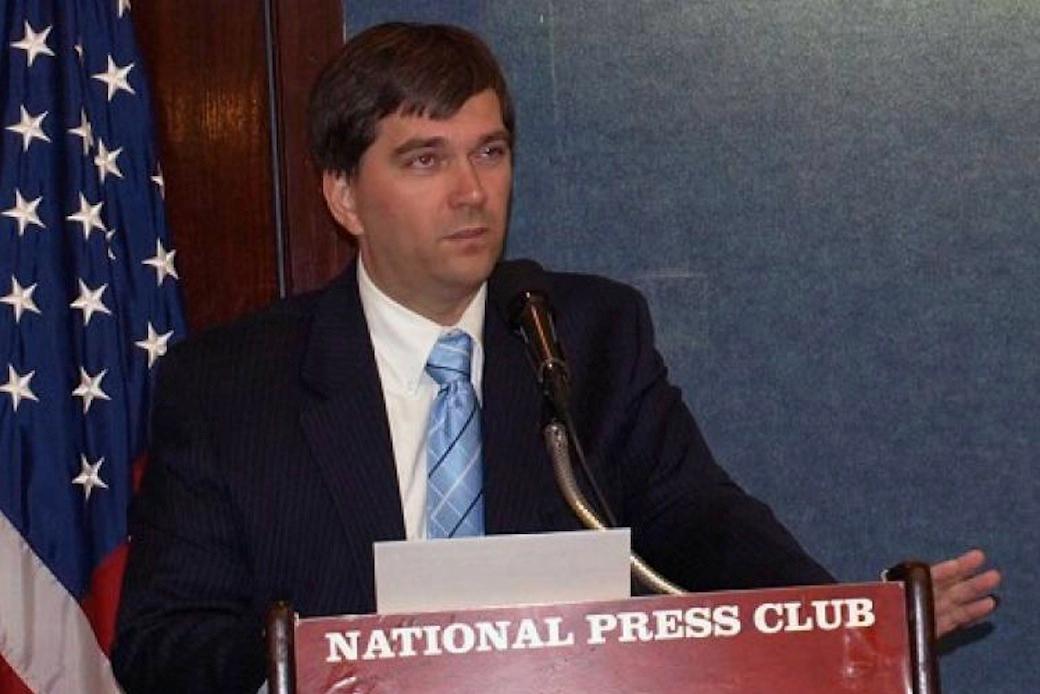

“The book should inform medical professionals, politicians, and everyone involved in providing information to the public,” Trey said in an interview in Washington, DC, soon after the book’s publication.

The medical community has a core interest in the matter because they are unwittingly training Chinese surgeons that then fly home and, potentially, help kill prisoners of conscience for their organs, he said. “How would you feel as the doctor who has taught this person? All the professors at universities need to know that this can happen.”

While the medical community needs to be sure that China’s organ sourcing practices do not “pollute the standards of medicine worldwide,” the questions raised by the volume at some level require political action by Western leaders.

The allegations and growing set of evidence presented in the book have been a matter of public record since 2006, and little has been done. “I don’t understand why, now for more than 6 years, there has been this silence and absence of curiosity,” Trey says, referring to major Western governments and institutions, who have failed to seriously probe the story.

“Maybe they think that if they look further into the subject, they would find that our suspicions are correct, then it would generate the necessity to react. And this is reacting towards China,” Trey said.

“But we’re talking about live organ harvesting, people killed for their organs. In the 21st century, this is not acceptable.

“Maybe there is fear at play into looking at the truth of the allegations,” Trey said.

One of the most striking features of the book is its title and cover art. Two pairs of feet, clad in hospital-blue cover-shoes, are presumed to belong to doctors looking over a patient at a hospital bed. The curtain is drawn. The top of the picture is never visible; instead are the words, right where the patient should be laying: State Organs: Transplant Abuse in China.

Trey says the symbolism was deliberate. “We want to refer to the fact that in the case of harvesting of organs from prisoners of conscience in China, state institutions are involved. The Communist Party is claiming the organs of its citizens as its own property. This is kind of unbelievable, that the individual integrity of the person is violated even to that point, that the person does not have the right to their own organs.”